BAL Leading the Way Series

How a chance meeting and the harnessing of big data led to a research initiative that’s finding answers in Lyme and tick-borne disease

Many different groups comprise the Lyme disease community including patients, their families, healthcare providers, researchers and nonprofit organizations. These nonprofit organizations and foundations may differ in size, structure, fiscal basis, focus and approach, but in one important aspect they are united: the search for answers.

This search for answers in the realm of Lyme and tick-borne diseases has served as a unifying driver, even when dissent and controversy has sometimes fragmented the Lyme community. And despite what seems to be a constant uphill battle for recognition and legitimacy of Lyme and tick-borne infections, many believe that we’re on the brink of major breakthroughs to help patients and doctors unlock the medical mysteries that make these infectious diseases so confounding. Two people cautiously optimistic about where we are in the search for answers about Lyme are Liz Horn, PhD, MBI, Principal Investigator, Lyme Disease Biobank, and Lorraine Johnson, JD, MBA, Chief Executive Officer, LymeDisease.org and Principal Investigator MyLymeData.

Back in 2014, Liz was hired by Bay Area Lyme Foundation (BAL) to run its fledgling Lyme biorepository initiative. This early stage biorepository program had been conceived in direct response to feedback from medical researchers who wanted to work in the field of Lyme, but couldn’t get access to enough patient samples to use in their research. Liz had previously worked in the field of rare disease helping organizations build patient registries and biobanks, so she was familiar with medical conditions like Lyme that don’t get the attention of big pharma and government resources. With Liz at the helm, pilot sample collection sites on Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard got quickly underway and BAL earmarked funds to launch a patient registry based on Liz’s strong recommendation. Liz was adamant that this would be an essential part of a biorepository program and began this patient registry evaluation early in the biobank development process. Lorraine Johnson at the time was, and still is, CEO of LymeDisease.org, but she was also a Lyme patient, driven to find answers for herself and others.

Back in 2014, Liz was hired by Bay Area Lyme Foundation (BAL) to run its fledgling Lyme biorepository initiative. This early stage biorepository program had been conceived in direct response to feedback from medical researchers who wanted to work in the field of Lyme, but couldn’t get access to enough patient samples to use in their research. Liz had previously worked in the field of rare disease helping organizations build patient registries and biobanks, so she was familiar with medical conditions like Lyme that don’t get the attention of big pharma and government resources. With Liz at the helm, pilot sample collection sites on Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard got quickly underway and BAL earmarked funds to launch a patient registry based on Liz’s strong recommendation. Liz was adamant that this would be an essential part of a biorepository program and began this patient registry evaluation early in the biobank development process. Lorraine Johnson at the time was, and still is, CEO of LymeDisease.org, but she was also a Lyme patient, driven to find answers for herself and others.

Serendipitously, Liz and Lorraine met at the PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) conference in the fall of 2015 and made an immediate connection. Congress had recently established and funded PCORI to usher in a new era of big data research that viewed patients as the center of the research equation through its PCORnet project. Lorraine was serving as a patient representative on the Executive Committee of PCORnet. Her goal was to obtain the expertise to launch a patient registry for the Lyme community.

Serendipitously, Liz and Lorraine met at the PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) conference in the fall of 2015 and made an immediate connection. Congress had recently established and funded PCORI to usher in a new era of big data research that viewed patients as the center of the research equation through its PCORnet project. Lorraine was serving as a patient representative on the Executive Committee of PCORnet. Her goal was to obtain the expertise to launch a patient registry for the Lyme community.

“One of the things that I recall from my very first conversation with Liz was that we were both completely focused on how we could lift the Lyme community and move it forward,” says Lorraine. “LymeDisease.org had been conducting and publishing patient surveys for over ten years, but we wanted to take that work to the next level by creating a patient registry to build an accessible platform and knowledge base that would continue to accumulate and bring value to the research community. As I talked with Liz, it was clear that she knew a lot about patient registries from her work in rare disease and her new role with Bay Area Lyme’s biorepository program provided us with a unique opportunity to collaborate in Lyme disease and expand the knowledge base.”

Adds Liz, “I knew from my rare disease work the incredible importance of the patient’s voice and the relevance of their lived experience. Developing a patient registry is a powerful tool as a starting point for medical information leverage. When you’re dealing with what’s in essence a ‘disadvantaged disease,’ where there isn’t enough research attention, patients and families cannot simply sit on their hands—they have to build the tools and resources needed so researchers can study their disease.” Lorraine agrees and further elaborates the objective, “Essentially, patients have to be willing to seize the oars and row the boat themselves.”

From their initial connection, Liz and Lorraine embarked on many conversations and meetings to explore how best to link the MyLymeData(MLD) patient registry to BAL’s growing Lyme Disease Biobank(LDB) in a spirit of collaboration, not competition.

Rather than have BAL reinvent the wheel and create a competing patient registry, it made sense to develop a long-term collaboration. The LDB had been founded and launched with initial funding of $1m raised by Bay Area Lyme Foundation, plus additional monies from a Fund-A-Need initiative at the foundation’s 2014 annual LymeAid gala. BAL had focused the LDB on the expensive and logistically complex task of developing in-person collection sites for patients to give blood, urine and—eventually—tissue samples, whilst MLD placed efforts on outreach to the Lyme community to encourage people to create profiles in the online registry—discrete, yet critical activities that would provide the basis for future research and discoveries.

“Fundamentally, BAL and MLD agreed to build a Lyme disease knowledge-base piece by piece,” explains Lorraine. “We knew from looking at other research databases that information is typically dumped in silos. This means that the data collected may be only relevant to a single study, valuable for a relatively short period of time, and accessible to the small groups of people—usually researchers—who “own” individual pieces of the data puzzle that remain unconnected. We wanted to collaborate on something that was patient driven where dynamic, accessible and constantly evolving data was created and would accumulate over time. This data would become increasingly useful to researchers, but the community would be able to control its use to ensure that research using patient data was conducted by trusted researchers for the benefit of patients.” Liz comments thoughtfully, “Back in 2014, when I was relatively new to the field, I noticed there were many entities in the Lyme community, but often these groups didn’t seem to be working together toward a common goal. From my experience in rare disease, I knew that groups working together were often more successful in creating research initiatives, and fractured groups typically were not able to move the field forward. When Lorraine and I met, we felt it was time to change the dynamic and that our organizations would be stronger together.”

Liz and Lorraine knew that they needed to borrow an approach that had proved to be successful from the rare disease communities. Each was running a discrete yet complementary entity that needed to be linked together in a partnership to solve the Lyme disease problem: 1. a patient registry and 2. a biorepository. The challenge was figuring out how to link them, and yet simultaneously give patients autonomy and the choice to share their data, as well as choices about how their information would be shared and used. And that’s how the Lyme Disease Biobank and MyLymeData online registry came to be connected, providing well-characterized samples with robust data to researchers.

Liz and Lorraine knew that they needed to borrow an approach that had proved to be successful from the rare disease communities. Each was running a discrete yet complementary entity that needed to be linked together in a partnership to solve the Lyme disease problem: 1. a patient registry and 2. a biorepository. The challenge was figuring out how to link them, and yet simultaneously give patients autonomy and the choice to share their data, as well as choices about how their information would be shared and used. And that’s how the Lyme Disease Biobank and MyLymeData online registry came to be connected, providing well-characterized samples with robust data to researchers.

But what does this mean?

“In traditional biorepositories or biobanks, blood, urine, and tissue samples are collected in-person, but the clinical information and data is often limited to what information is collected at the time the sample is collected. In-person sample collection is expensive and time-consuming, yet getting people to show up and physically give samples is absolutely at the heart of what has to happen. We wanted to go a step further and provide researchers with well-characterized samples,” Liz goes on to explain. “What this means is that we wanted to identify additional sources of information and link the samples to information BEYOND what’s collected when the physical sample is collected which is—afterall—a ‘snapshot in time’ based on when that sample is collected. Life isn’t just a point in time, like a photograph. It’s more like a movie—continually moving and changing. While the Biobank collects information at the time of sample collection about symptoms, tick exposure, health history, and current medication, MyLymeData is able to collect more detailed information that extends beyond one time point or snapshot because people can participate online and continually update information from the comfort of their home computer. With MyLymeData, we can leverage other important ongoing information about the person who made the effort to come to one of Lyme Disease Biobank’s collection sites and physically provide samples. We get a lot more than a snapshot. We get whole chapters in the story of the person’s disease progression,” she notes. “This is really important for trying to understand complex diseases like Lyme and other tick-borne diseases and more involved samples like surgical or post mortem tissue samples. The power is in tying these two together.”

“In traditional biorepositories or biobanks, blood, urine, and tissue samples are collected in-person, but the clinical information and data is often limited to what information is collected at the time the sample is collected. In-person sample collection is expensive and time-consuming, yet getting people to show up and physically give samples is absolutely at the heart of what has to happen. We wanted to go a step further and provide researchers with well-characterized samples,” Liz goes on to explain. “What this means is that we wanted to identify additional sources of information and link the samples to information BEYOND what’s collected when the physical sample is collected which is—afterall—a ‘snapshot in time’ based on when that sample is collected. Life isn’t just a point in time, like a photograph. It’s more like a movie—continually moving and changing. While the Biobank collects information at the time of sample collection about symptoms, tick exposure, health history, and current medication, MyLymeData is able to collect more detailed information that extends beyond one time point or snapshot because people can participate online and continually update information from the comfort of their home computer. With MyLymeData, we can leverage other important ongoing information about the person who made the effort to come to one of Lyme Disease Biobank’s collection sites and physically provide samples. We get a lot more than a snapshot. We get whole chapters in the story of the person’s disease progression,” she notes. “This is really important for trying to understand complex diseases like Lyme and other tick-borne diseases and more involved samples like surgical or post mortem tissue samples. The power is in tying these two together.”

So, how do the Lyme Disease Biobank and MyLymeData patient registry actually work together?

“If you are a Lyme patient, you can go on to MyLymeData and create a profile,” says Lorraine. “Patients with Lyme disease tell us about their experiences, symptoms, treatments, and results. Periodically, they update their information to let us know what has changed. This allows us to better understand the progression of the disease and what works—and what doesn’t work—to help people get better. It lets patients learn from each other and provides data that can drive research to improve patients’ lives.”

“Then, if a participant decides to participate in the Lyme Disease Biobank, they have the option to LINK their samples directly to information in their MyLymeData profile,” adds Liz. “This is what’s so powerful about our collaboration—and the participant has complete control over how that information is shared. If samples go out from the LDB, they are always de-identified (i.e. the researcher never sees the name or any kind of identifying information, including HIPAA identifiers, about the participant), but that additional information can really help researchers understand what’s happening in a person’s immune system at a much deeper level. MyLymeData is the steward of the data in the MyLymeData registry, and determines what information to provide to the researcher.”

“Then, if a participant decides to participate in the Lyme Disease Biobank, they have the option to LINK their samples directly to information in their MyLymeData profile,” adds Liz. “This is what’s so powerful about our collaboration—and the participant has complete control over how that information is shared. If samples go out from the LDB, they are always de-identified (i.e. the researcher never sees the name or any kind of identifying information, including HIPAA identifiers, about the participant), but that additional information can really help researchers understand what’s happening in a person’s immune system at a much deeper level. MyLymeData is the steward of the data in the MyLymeData registry, and determines what information to provide to the researcher.”

By 2016, with proof-of-concept firmly established, the next key objective for Bay Area Lyme’s priority project was growing the network of physical collection sites, increasing the volume of patient samples for research, and launching a much-needed tissue donation program. Ramping up the number of patient samples would require a significant injection of funding. Bay Area Lyme Foundation already had a relationship with The Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation; they understood the need and generously granted the game-changing multi-year $5M funds to take the LDB program to the next level.

By 2016, with proof-of-concept firmly established, the next key objective for Bay Area Lyme’s priority project was growing the network of physical collection sites, increasing the volume of patient samples for research, and launching a much-needed tissue donation program. Ramping up the number of patient samples would require a significant injection of funding. Bay Area Lyme Foundation already had a relationship with The Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation; they understood the need and generously granted the game-changing multi-year $5M funds to take the LDB program to the next level.

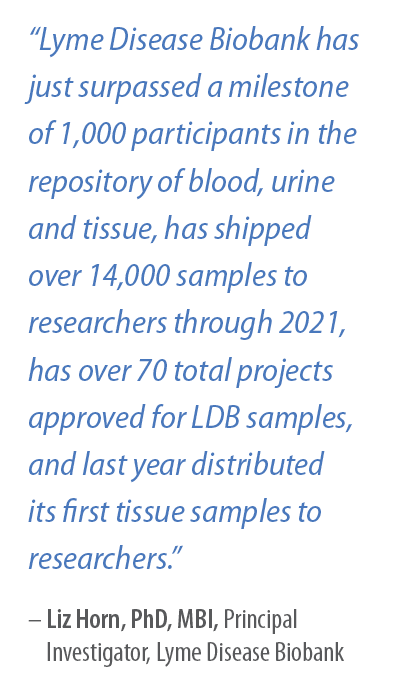

As of writing this blog, the Lyme Disease Biobank has surpassed a milestone of 1,000 participants in the repository of blood, urine, and tissue. “Since our launch, we have shipped over 14,000 samples to researchers through 2021, and last year we distributed our first tissue samples to researchers. We have over 70 total projects approved for LDB samples, and this number is increasing. We have published on the characterization of our early Lyme samples (1), and scientists have published six studies using LDB samples, with more to come. The Biobank is the fuel that’s feeding the research engine, and it’s starting to yield results,” says Liz with a smile.

And, since its launch in November 2015, MyLymeData has enrolled over 16,000 online participants in the MLD database—far outstripping any previous attempt to gather information on Lyme patients. Five patient-led research publications from the registry have been published. MyLymeData expects to gather more data about Lyme disease patients than any other research study, and has demonstrated this by exploring treatment effects in MLD participants (2). As a point of comparison, the four Lyme disease treatment trials funded by the National Institutes of Health enrolled fewer than 100 patients each in the treatment group (3). Plus, when MyLymeData was launched, people thought that Lyme co-infections were rare, but as Lorraine explains, “What we’ve discovered with MyLymeData confirms what we were hearing anecdotally: coinfections among the persistent/chronic Lyme patients are NOT rare, and we can prove this through data collected through the registry and through the specimens collected by the LDB.”

And, since its launch in November 2015, MyLymeData has enrolled over 16,000 online participants in the MLD database—far outstripping any previous attempt to gather information on Lyme patients. Five patient-led research publications from the registry have been published. MyLymeData expects to gather more data about Lyme disease patients than any other research study, and has demonstrated this by exploring treatment effects in MLD participants (2). As a point of comparison, the four Lyme disease treatment trials funded by the National Institutes of Health enrolled fewer than 100 patients each in the treatment group (3). Plus, when MyLymeData was launched, people thought that Lyme co-infections were rare, but as Lorraine explains, “What we’ve discovered with MyLymeData confirms what we were hearing anecdotally: coinfections among the persistent/chronic Lyme patients are NOT rare, and we can prove this through data collected through the registry and through the specimens collected by the LDB.”

As they look ahead, both Lorraine and Liz are focusing their attention on what else the research engine can do and how they need to expand it. “We’re excited about the potential to collaborate more extensively with researchers and new research organizations that may be formed in the future—such as clinical data research networks formed by those healthcare providers who treat Lyme disease,” explains Liz. “These types of collaborative efforts could break down the data silos that impede research progress. With more groups helping to ‘row the boat,’ we can accelerate the pace of research and innovation in the community.”

Liz Horn and Lorraine Johnson joined forces a few years ago and built a Lyme research engine to address significant challenges, including the need for better diagnostics and therapeutics. The two organizations are confident this effort will lead to uncovering some of the most intractable and perplexing challenges within the Lyme community. “There’s power in numbers. Patients not only contribute data to the knowledge-base, they also can drive research recruitment efforts—already MyLymeData has been involved in recruitment for two research studies. We believe that we have built a model of trust, collaboration and hope. We’re extremely proud of that,” Lorraine emphasizes. And Linda Giampa, Executive Director of Bay Area Lyme Foundation adds, “It’s the patients who are the heroes in this story. We are fueling the research engine for patients by patients. By engaging and collaborating with thousands of patients directly, building a circle of trust, and putting information-sharing power and control into the hands of patients, we can drive progress.”

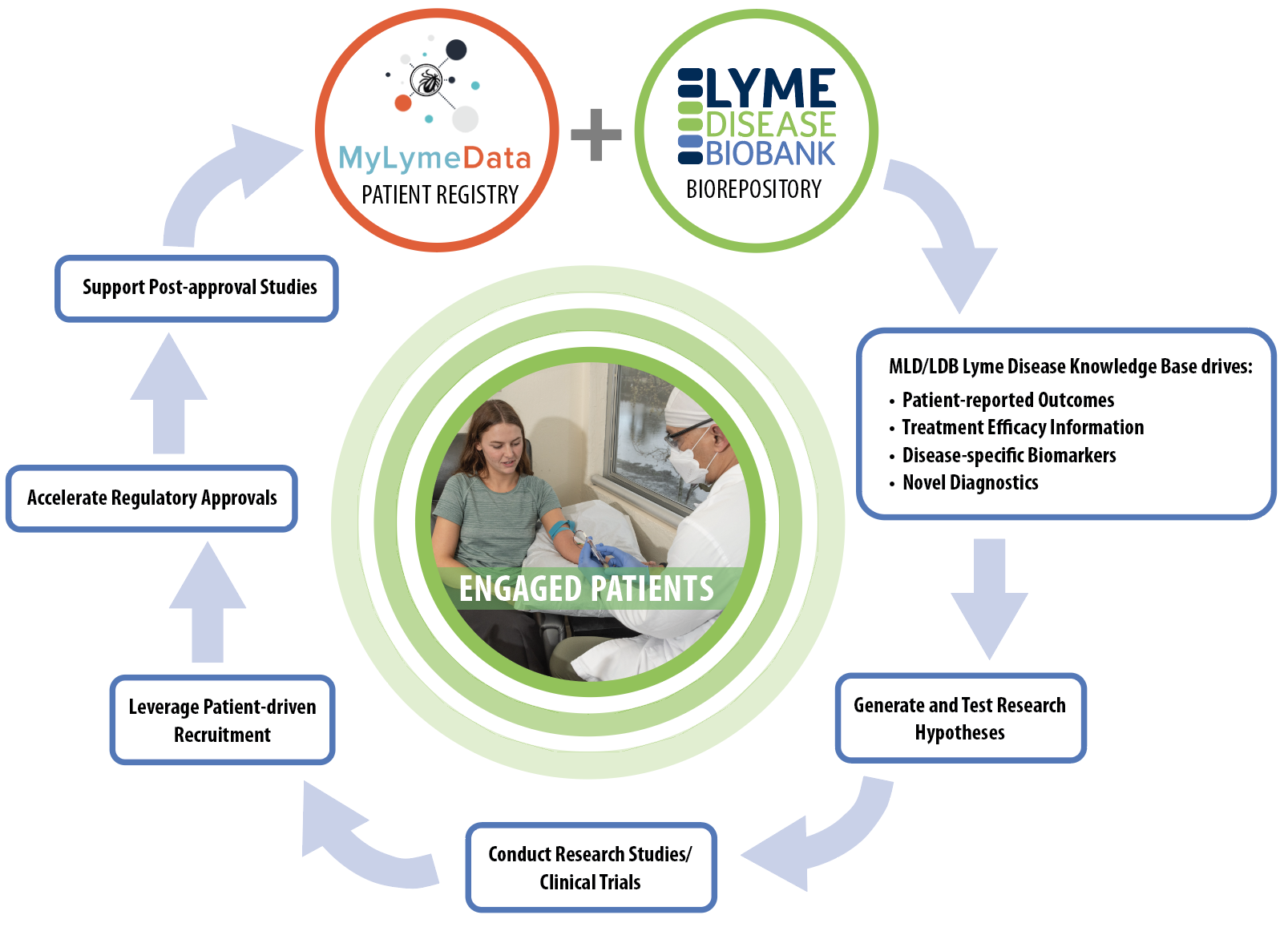

The Patient-driven Research Engine: a key tool for progress in Lyme disease research. The MyLymeData (MLD) patient registry and Lyme Disease Biobank (LDB) biorepository offer opportunities for patients/people with Lyme disease to participate in research. These resources (MLD and LDB) form a disease knowledge base that can be used to identify clinical outcome measures (endpoints for research studies and trials), understand treatment efficacy (how well a treatment works or doesn’t work), and identify biomarkers (molecules that are specific to a disease process) and novel diagnostic tests. This knowledge base is used to develop research hypotheses (research questions) that can be tested in research studies and clinical trials. Engaged patients are needed to speed recruitment for research studies and clinical trials through patient-driven recruitment and outreach efforts. This will lead to new and accelerated regulatory approvals and ultimately post-approval studies, which occur once a treatment is already approved. Engaged patients are at the center of this iterative process. Their authentic engagement allows the research engine to continue to ignite and accelerate research, and improve the lives of people with Lyme disease. This Bay Area Lyme Foundation blog is part of our BAL Leading the Way series. Bay Area Lyme provides reliable, fact-based information so that prevention and the importance of early treatment are common knowledge. For more information, including our research and prevention programs, go to www.bayarealyme.org.

Bibliography

- Horn, Elizabeth J., et al. “The Lyme Disease Biobank: Characterization of 550 Patient and Control Samples from the East Coast and Upper Midwest of the United States.” Journal of Clinical Microbiology, vol. 58, no. 6, 2020, https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jcm.00032-20

- Johnson, Lorraine, et al. “Removing the Mask of Average Treatment Effects in Chronic Lyme Disease Research Using Big Data and Subgroup Analysis.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 12 Oct. 2018, https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6040124

- Delong, Allison, et al. “Antibiotic Retreatment of Lyme Disease in Patients with Persistent Symptoms: A Biostatistical Review of Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Clinical Trials.” Contemporary Clinical Trials, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22922244/