BAL Leading the Way Series

“The opening of a network of Lyme disease clinics is the culmination of many years of tireless work and the vision of a small group of determined women over 10 years ago. We are extremely optimistic that the Lyme Clinical Trials Network will accelerate the development of new treatments for patients with post-treatment and persistent Lyme disease.”

—Linda Giampa, Executive Director, Bay Area Lyme Foundation

When Bay Area Lyme Foundation (BAL) was formed a decade ago, its mission was clear: to make Lyme disease easy to diagnose and simple to cure. “And that’s still our goal,” emphasizes BAL co-founder Bonnie Crater, as she reflects on the last 10 years. However, appreciating the magnitude of the Foundation’s audacious mission requires an understanding of two complex—yet inextricably linked—medical domains: the world of diagnostics, and the world of therapeutics.

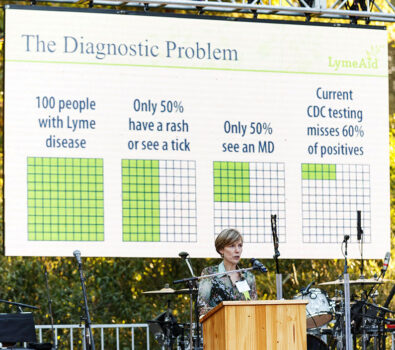

The ‘Holy Grail’ for Lyme disease is an accurate diagnostic test—or better yet a suite of specifically designed tests for the different stages of acute and persistent Lyme disease. Although great strides are being made in understanding the infection and the disease’s progression, the ‘silver bullet’ of accurate diagnostic tests continues to elude us. The current diagnostics for acute Lyme (a two-step process with an ELISA either followed by a Western blot or another ELISA) are fraught with problems. These tests may miss up to 70% of acute Lyme cases or deliver false negative results. They are unreliable for detecting acute Lyme and are ineffective indicators for anyone with a persistent/chronic tick-borne infection. (Watch or listen to our Ticktective with Brandon Jutras, PhD, to learn why the current direct detection tests for Lyme are so inaccurate.)

Add to this the fact that FDA-approved therapeutics—or ‘cures’—have not evolved much in 10 years either and foment controversy. A quick internet search on ‘How to treat Lyme disease’ will offer information from the IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America) stating that a 10-14-day course of oral antibiotics, such as amoxicillin or doxycycline, will do the job for someone with an EM (Erythema migrans) rash who has early/acute Lyme. But anyone who has had Lyme disease, been treated, and then experienced a continuation of symptoms knows that this recommended course of intervention often fails to clear the infection, leaving some persistent Lyme patients in limbo, and health care providers without an approved treatment protocol. Simply put, this is the continuing underlying treacherous terrain of Lyme, throwing up challenges in both diagnostics and therapeutics.

Going back to 2012, despite not having an accurate diagnostic, the BAL team were determined to lay the groundwork required for the possibility of a future clinical trial. It was the ultimate leap of faith. Although very early in the game (the Foundation had only just been formalized), the team was already talking about embarking on an extremely complex, highly regulated, and expensive project.

“We talked about a clinical trial in our first BAL meeting, knowing that it’s very difficult to undertake a clinical trial when a) you don’t know whom to enroll, b) who actually has the disease, and c) when they’re cured. It’s like trying to hit a target blindfolded,” recounts Wendy Adams, the Foundation’s Research Grant Director.

“I know – it sounds crazy,” Bonnie adds, wryly. “Yet, we knew we were in this fight against Lyme disease for the long haul. We also knew that the horizon for developing accurate diagnostics for both acute and persistent Lyme was a very long way off. Plus, developing new drugs and getting them FDA approved is, of course, insanely expensive and can take many, many years,” she notes. Yet, despite these seemingly insurmountable odds, BAL was determined to proceed with an unconventional, yet bold strategy.

At this time, therapeutics for Lyme were all over the map. However, Bonnie, Wendy, and the rest of the team believed there was a possibility that existing FDA-approved drugs might be effective at treating both early and later-stage/persistent Lyme, either as stand-alone therapeutics, or as multi-drug combinations. “Only one published study had explored some of the tens of thousands of available, FDA-approved drugs at this point,” Bonnie adds. “We decided to approach the problem from this new angle and thought we might make some discoveries that could help people suffering with Lyme.” And as is often the case with protracted, complex projects, progress happened in uneven phases and featured a rotating cast of key characters.

Part 1: What’s in the Current Pharmaceutical Arsenal?

Enter Jayakumar “Jay” Rajadas, PhD, currently Director, Advanced Drug Delivery and Regenerative Biomaterials Laboratory (ADDReB) of Cardiovascular Institute (CVI), Stanford University School of Medicine. Jay’s proposal was to leverage an assay (that’s science speak for a test) which would measure the borreliacidal effects (that’s the killing effect on Borrelia) of approximately 4,000 existing FDA-approved drugs to see if any of them would kill Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb) in a test tube.

There were many potential benefits of embarking on this particular experiment, which Bonnie calls Part 1 of the clinical trial story. “Firstly, it’s important to be very clear about how incredibly serious any kind of clinical trial involving human subjects is. There are extremely stringent laws in place regarding consent, safety, and vulnerable populations, so we knew that these existing FDA-approved drugs had already passed rigorous safety standards and had been tested in humans. That was a big plus. Secondly, as a small foundation, BAL had limited funding resources and had only been in existence for a short amount of time. Furthermore, any new therapeutics discovery efforts were multiple years away from being ready for testing in patients. Thirdly, Dr. Rajadas’s lab was literally down the road from us at Stanford University, so we had tremendous access and ease due to geographical proximity.”

“We decided to approach the (therapeutics) problem from a completely different angle and thought we might make some discoveries that could help people suffering with Lyme. No-one had explored the thousands of available, FDA-approved drugs yet.”

–Bonnie Crater, Co-Founder, Bay Area Lyme Foundation

At about the same time, Ying Zhang, a young post-doctoral researcher at Johns Hopkins University, had launched a similar study testing 2,000 available drugs. And later in 2015 Kim Lewis, University Distinguished Professor and director of Antimicrobial Discovery Center at Northeastern University, published a study establishing that Bb formed persister cells and some FDA approved antibiotics were able to kill Bb in a persistent form in the lab. Kim Lewis used a different protocol and different assays than Dr. Zhang and Dr. Rajadas. Ultimately, even with these different approaches, the goal was the same: to discover if any compounds or combinations of existing drugs are effective at killing Lyme in vitro (in a test-tube).

So, by the end of 2016, these three independent studies by Rajadas, Zhang, and Lewis discovered that there were in fact FDA-approved drugs that had a deleterious effect against Bb, though these studies were in the laboratory and not on human subjects. Some of these drugs included azlocillin, disulfiram, and loratadine. Both individual drugs and drugs in different combinations were shown to kill Lyme in vitro, but that didn’t mean that BAL could announce this to the world and inspire health care providers to prescribe these medications to Lyme patients. The fact that these were already approved did not diminish the enormous responsibility that scientists undertake when developing any kind of drug protocol or treatment for humans. And things were about to get even more complicated.

Part 2: So, Who Gets Included in a Clinical Trial?

Encouraged by the preliminary findings that there were drugs already available that could potentially improve the lives of people suffering from Lyme disease, the BAL team thought the next phase could be to launch a clinical trial to explore how to test these findings in humans— which seemed like the next logical step.

“Like everything to do with testing on humans—even using already approved drugs—we had to be slow, careful, and deliberate in our approach,” cautions Bonnie. “The big challenge now was agreeing on a protocol for testing these drugs in humans… and without an accurate diagnostic tool that proves without a doubt that someone HAS an infection or disease, how do you reliably select patients to be included in a drug trial? It’s not just about inclusion and exclusion, but also what is referred to as the ‘endpoint question.’ How do you resolve people’s symptoms? What’s the test by which you’re going to tell if somebody’s cured and if it’s the intervention that has cured them?”

With entrenched disagreement on determining who has Lyme and who doesn’t have Lyme among healthcare providers—never mind the CDC and NIH—it was clearly an enormous challenge trying to figure out how to make this happen.

The BAL team decided to assemble a panel of 10-15 Lyme experts to devise a consensus-driven protocol for a future clinical trial. The plan was to ask those gathered to outline what they thought the parameters for a clinical trial should be—to develop an open ‘blueprint’ as it were for all clinicians and researchers seeking to develop new therapeutic regimens for Lyme.

The objective was to collect the panel’s input, then follow-up with surveys to clarify remarks and findings. “We were really looking forward to experiencing the benefits of having everybody in the same room talking about these complicated issues in real time, instead of writing papers back and forth, or reading position papers from the NIH,” Wendy recounts.

Washington DC was picked as the location for the meeting, and leaders from within the Lyme world—researchers, clinicians, representatives from the NIH and IDSA, etc.—were invited to this inaugural Lyme Clinical Trial Summit in March 2017. Bonnie recruited Liz Horn, PhD/MBI (now Principal Investigator of BAL’s Lyme Disease Biobank), to run the one-day event.

“Right from the get-go, we knew we were going to have challenges,” recounts Liz Horn. “Everybody in the room was excited to be a part of this meeting and wanted to make positive contributions to what, ultimately, might be a ground-breaking leap forward for patients with persistent Lyme. Everyone in the room recognized that people with persistent Lyme were suffering, and health care providers were challenged in how to treat and help their patients. Lyme disease is incredibly complex and there are many unknowns. Given these challenges, it was extremely difficult to reach consensus, particularly around what Lyme diagnosis criteria to use to determine eligibility for a clinical trial.”

It boiled down to the one seemingly insurmountable and intractable challenge: the lack of an accurate diagnostic.

“Lyme disease is incredibly complex and there are many unknowns. Given these challenges, it was extremely difficult to reach consensus, particularly around what Lyme diagnosis criteria to use to determine eligibility for a clinical trial.”

– Liz Horn, PhD/MBI, Principal Investigator, Lyme Disease Biobank

Bonnie throws more light on the problem of creating a consensus around clinical trial protocol for Lyme disease, “When you’re looking at a population of people who have persistent Lyme, do you include people who have had one course of antibiotics and failed to recover? Or two courses? Or multiple rounds? Or do you include those who have never had antibiotics at all? Plus, as we know, some people never once become seropositive (medical speak for getting a positive blood test) for Lyme in the entire course of having this disease. This makes developing a clinical trial protocol very challenging.”

“Turns out that if you don’t have an effective, accepted, accurate diagnostic that can prove who has Lyme and who doesn’t have Lyme, it’s almost impossible to agree on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for a clinical trial,” expands Liz. “Plus, if you have people who have been diagnosed with chronic/persistent Lyme by a clinician, but there’s no test to confirm that, then how do you agree who can be part of a clinical trial that’s designed specifically to test drugs on a group of patients with that disease? Especially when the ramifications of the trial’s outcome might negatively impact the health of other patients. It’s an extraordinary conundrum.”

Like everything else in the ecosphere of Lyme disease, nothing is simple. Without clearly agreed-upon inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and outcome or ‘endpoint’ measures, or even what the optimal medical intervention should be—an antibiotic, combination of antibiotics, or something else—the BAL team could have been forgiven for succumbing to defeat. And yet, out of debate and dissent, sometimes positive things can emerge. In this case, the team went back to the West Coast and pondered their findings. “After many conversations and additional surveys of the experts, what we ultimately decided was that without an agreed-upon consensus/protocol on how to test this shortlist of possible drugs on people with Lyme, we should hit the pause button on a human clinical trial for the time being and explore some other research avenues,” explains Liz. “We needed to regroup.”

Nevertheless, Bay Area Lyme pushed forward, and the team continued to discuss how best to proceed, revisiting their findings at intervals and checking in with the science community on ideas and options. They still had a shortlist of drugs identified by the three independent researchers that had been shown to kill or negatively affect Bb in test tubes. This was something worthy of further exploration, and eventually, another distinct waymark was reached on this winding journey: The Mouse Studies—aka Part 3.

Part 3: Why Relationships Between People, Scientists, and Mice Matter—and How a Random Anti-alcoholism Drug Helped the Cause

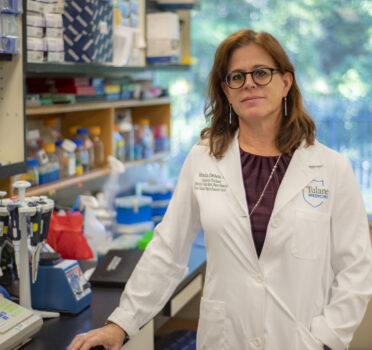

Dr. Monica Embers of Tulane University and BAL already had a long and fruitful research history together. Embers’s ground-breaking work showing that the Borrelia bacteria can persist even after antibiotic treatment helped validate many patients who had suffered for years with Lyme only to be told repeatedly, ‘It’s all in your head.’ So, it made sense for BAL to team up with her on this new project. Bonnie recounts, “We reached out to Dr. Embers and said, ‘We’ve got this list of drugs that we think might be able to tackle persistent Lyme. Other researchers are getting encouraging results in vitro. Should we test these findings in mice?’ Of course, our conversations were much more formal and involved appropriate paperwork regarding grant monies, deliverables, timelines, etc.,” Bonnie adds, “but essentially, we leveraged our existing relationship with Dr. Embers to explore whether mice studies would be a logical step.”

In 2018, Dr. Embers embarked on several different projects with a list of possible drugs to test on mice using a persistent Lyme disease model to see if any might be of interest as possible therapeutics. “Therapeutics can do a number of things,” Bonnie notes, carefully. “They might make people feel better, despite not tackling the underlying infection by reducing inflammation, for example, or they might actually reduce infection to the point where a patient is symptom-free. However, neither of these may actually be a ‘cure’ where the bacteria are eradicated from the body. So, although we were optimistic that some of the available drugs from our shortlist of possibilities might make Lyme patients feel better, we saw this as a short-term step while still focusing on our long-term mission to make Lyme disease easy to diagnose and simple to cure.” Dr. Embers’s mouse studies were designed to test whether these FDA-approved drugs could eradicate the Borrelia bacteria in a persistent Lyme disease model.

However, some providers with significant experience of treating Lyme patients had already taken matters into their own hands and had been experimenting with novel therapeutic strategies aimed at eliminating stealth tick-borne infections. One such clinician was Dr. Steven Phillips. Knowing Dr. Embers’s earlier work (proving that persistent pathogens were evading the conventional therapeutic approach), he had already been combining existing FDA-approved drugs to see if suffering was alleviated in his patients, but it was impossible for him to learn much beyond a patient’s own personal, subjective experience. For instance, if a patient anecdotally reported a reduction in symptoms, it was impossible to measure the medical efficacy of these approaches without an accurate test to prove their reportage. In 2018, Bay Area Lyme Foundation awarded an Emerging Leader Award to Dr. Phillips so that he could test compounds in vitro to determine whether they had a superior efficacy against conventional standard-of-care therapeutics.

Meanwhile, in 2019, a physician in NY state, Dr. Kenneth Liegner, had also been exploring new Lyme disease treatment options (with the consent of approximately 70 of his persistent Lyme patients), using FDA-approved drugs off-label. The impetus for this came from one of Dr. Leigner’s own Lyme patients. The patient had heard Dr. Kim Lewis from Northwestern University (mentioned earlier in this article), discuss Dr. Jay Rajadas’s BAL-funded work where he explored using FDA-approved drugs as potential Lyme therapeutics. One of these drugs was disulfiram—typically used as an anti-alcoholism treatment.

Dr. Liegner started prescribing disulfiram to treat Lyme and babesiosis with some success, and his findings were noted with a degree of excitement within the Lyme ecosphere. One of Dr. Liegner’s patients declared himself symptom-free from Lyme and babesia as a result of taking disulfiram, leading to excited chatter within Lyme patient circles. The challenge was that this activity was not a formal clinical trial, and therefore could not qualify as a formal study. And yet, Dr. Liegner’s activity, driven by the desire to help his persistent Lyme patients, helped bolster the case for a robust, carefully controlled study of already available FDA drugs to treat Lyme and tick-borne infections. As Bonnie interjects, “It proved that Jay Rajadas had definitely been on to something right from the get-go—we just needed to be able to conduct more carefully controlled experiments.” (Watch or listen to our Ticktective with Kenneth Liegner, MD, to learn about his experiences treating Lyme patients with disulfiram.)

Part 4: If You Build It, They Will Come: A New Lyme Clinical Trials Network is Announced

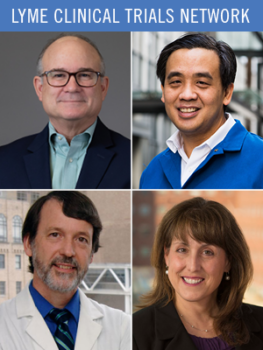

At the same time as Dr. Liegner’s off-label explorations of FDA-approved medications were underway, another key organization that had been creating opportunities for researchers in the Lyme field, began moving to the forefront, laying the foundation for a future clinical trial infrastructure. The Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, a Connecticut-based nonprofit, had been funding Lyme research for a number of years, providing grants to researchers and engaging in preliminary clinical trials. Lyme research is a very tightly knit world, so there was considerable overlap between scientists who were being funded and supported by both The Cohen Foundation and Bay Area Lyme. Conversations were emerging organically about how to conduct national clinical trials, especially between individuals who would emerge as key players down the road, including Drs John Aucott and Charles Chiu. During the 2017 Bay Area Lyme summit meeting in DC, participants noted that in order to mount successful, collaborative clinical trials in the future, there had to be relationships and infrastructure in locations already in place across the country. Leveraging notable partner institutions, grantees, and approved researchers was the most obvious place to start. This network was needed to bring new treatments to the clinic faster and to help patients. Waiting for a potential drug that could be tested in humans, and then building a network of researchers and clinicians to test it, would slow down testing and analysis, potentially adding years to the endeavor.

“The Lyme Clinical Trials Network was created to help bring treatments and hope to Lyme disease patients and their families. We look forward to the continued growth of the Network and are excited to have UCSF join as the first West Coast site.”

– Alexandra Cohen, president of the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation

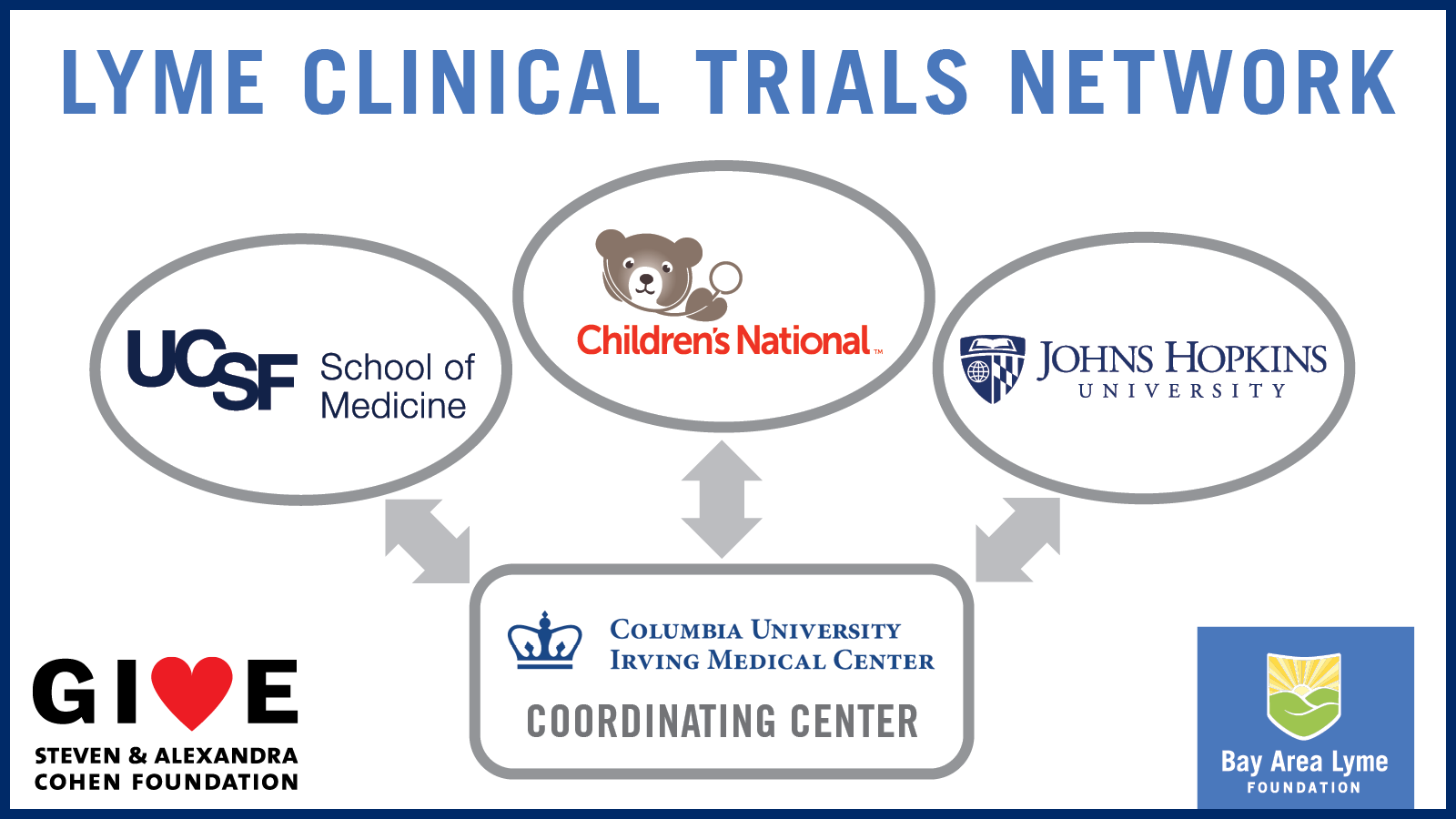

The Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation decided to invest $16 million into building a national clinical trial network, developing ‘hubs’ in key locations that would be the bases for future clinical trials. In 2019, they funded the Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center at Columbia University under the guidance of Dr. Brian Fallon, and in 2020, Johns Hopkins University and Children’s Hospital, under Dr. John Aucott, and Roberta Lynn DeBiasi, MD/MS, respectively, agreed to be ‘nodes’ that would support the Columbia hub.

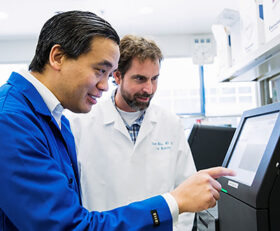

In 2022, Bay Area Lyme Foundation leveraged its long and fruitful connection with Dr. Charles Chiu, MD/PhD, and with the support of BAL funding, University of California San Francisco (UCSF) agreed to be the Cohen Foundation’s third ‘hub’ for the nascent clinical trial network with the West Coast’s Lyme Clinical Trial Center launch planned for 2023. “The Lyme Clinical Trials Network was created to help bring treatments and hope to Lyme disease patients and their families,” said Alexandra Cohen, president of the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation. “We look forward to the continued growth of the Network and are excited to have UCSF join as the first West Coast site.” The new center is currently being established, and the team is working to build a place where clinical trials for Lyme patients can be conducted. “The founding of the UCSF Lyme Clinical Trials Center provides a unique opportunity for Lyme patients to participate in the next generation of diagnostic and therapeutic trials to combat this devastating disease,” said Charles Chiu, University of California, San Francisco, who will lead the UCSF Lyme Clinical Trial Center. “Very few clinical trials have been initiated to investigate therapeutic solutions to address persistent symptoms of Lyme disease, and we hope to change this.”

“The founding of the UCSF Lyme Clinical Trials Center provides a unique opportunity for Lyme patients to participate in the next generation of diagnostic and therapeutic trials to combat this devastating disease. Very few clinical trials have been initiated to investigate therapeutic solutions to address persistent symptoms of Lyme disease, and we hope to change this.”

– Charles Chiu, MD/PhD, University of California, San Francisco, who will lead the UCSF Lyme Clinical Trial Center

The BAL team’s idea of testing already approved FDA drugs to help alleviate Lyme disease symptoms in the early days of the clinical trial objective was definitely an idea that has subsequently been proven to be a promising strategy in the absence of other reliable options for patients with persistent/chronic Lyme. But this has not obscured the ultimate goal of developing new therapies and drugs/compounds—including more potential investigation of herbal supplements which will make Lyme disease easy to cure. In the meantime, Dr. Embers will likely go on to develop a short-list of FDA-approved drugs that look like the most promising candidates from her animal studies. This will help to verify the drugs’ potential efficacy in treating persistent Lyme disease, prior to being earmarked as appropriate for a clinical trial in humans.

However, even after animal studies have been performed and data collected, without a reliable, widely distributed, accurate Lyme disease diagnostic tool, we still have to agree on who is eligible to be enrolled in a clinical trial. “Improvements in diagnostics—and more specifically direct diagnostics—will make clinical trial results more robust. While we have alternative ways of deciding who should be enrolled—by symptoms, or previous FDA cleared testing results, for example—we need to know who is still infected, and who may be ill due to some other, adjacent cause,” concludes Wendy Adams. Even so, elucidating which drugs—either individually or in combinations—can be effective against a persistent Lyme disease infection in mouse studies, Dr. Embers’s work will get Bay Area Lyme one step closer to determining the optimal therapeutics for persistent/chronic Lyme patients and future clinical trials in humans. “By working with the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, we are building the Lyme Clinical Trials Network, a network of clinics, clinicians, and researchers who are primed to test new therapies in humans. It’s a win-win-win,” comments Linda Giampa, executive director of Bay Area Lyme Foundation. “The opening of a West Coast clinical trial site at UCSF is the culmination of many years of tireless work and the fulfillment of the vision of a small group of determined women over 10 years ago. We are extremely optimistic that the Lyme Clinical Trials Network will accelerate the development of new treatments for patients with post-treatment and persistent Lyme disease.”

Although it’s been a long and winding road, there are many reasons for patients and advocates to be optimistic. These are major, significant leaps forward in putting together the infrastructure and planning to get drugs off the sidelines, out of the laboratory, and into human trials. Let’s hope that BAL’s concurrent work in researching and funding new diagnostics and the development of the Lyme Clinical Trials Network provides the key to this continuing dilemma and the cause of so much suffering for persistent Lyme and tick-borne disease patients.

This Bay Area Lyme Foundation blog is part of our BAL Leading the Way Series. Bay Area Lyme provides reliable, fact-based information so that prevention and the importance of early treatment are common knowledge. For more information, including our research and prevention programs, go to www.bayarealyme.org.

Hi

The latest research on Disulfiram (which many people have taken successfully) shows that the user of a new formulation using nanoparticles could alleviate some of the significant side effects of Disulfiram.

As it’s a drug already approved and just requires a formulation change, isn’t it wise to support some of this research to test its efficacy and side effects through Dr Liegner and Dr Rajadas whom you have mentioned in your article.

The patients have more knowledge on how to use Disulfiram safely currently but the new form will help those that are unable to take Disulfiram in its original form.

Regards

Joseph Kulandai

Administrator Bartonella and Lyme groups and International Patient Coordinating Group.

Melbourne.

Australia.