Ticktective Podcast Transcript

In this insightful conversation between Ticktective™ guest host Dana Parish and microbiologist Amy Proal, PhD, we investigate persistent pathogens, how they remain in the body after treatment often leading to chronic illness, and how they can be reactivated by new infections, including Covid-19. Note: This transcribed podcast has been edited for clarity.

Dana Parish: Welcome to the Ticktective Podcast, a program of the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, where our mission is to make Lyme disease easy to diagnose and simple to cure. I’m your guest host today, Dana Parish. I’m the co-author of the book Chronic, and I’m on the advisory board of Bay Area Lyme Foundation. This program offers insightful interviews with clinicians, scientists, patients, and other interesting people. We’re a nonprofit foundation based in Silicon Valley, and thanks to a generous grant that covers a hundred percent of our overhead, all your donations go directly to our research and our prevention programs. For more information about Lyme disease, please visit us at www.bayarealyme.org.

Today, on behalf of Bay Area Lyme Foundation, I am here with brilliant microbiologist Dr. Amy Proal. I have a little bio for her. I’m going to read right now. Dr. Proal serves as president and CEO of PolyBio Research Foundation, and she’s the chief scientific officer of the Long Covid Research Initiative, LCRI. She went to Georgetown, she has a PhD in microbiology from Murdoch University in Australia, and she is a rockstar in the field and a leader in the field of persistent pathogens. She has just come off of a huge press tour for her incredible work and the enormous grant that she just received for her Long Covid research, and I’m so excited to be one of the first people to talk to you after all this.

Amy Proal, PhD: Of course, Dana, thanks so much for having me. That was an amazing intro. I appreciate all of that. It’s great to be interviewed by you. It’s mostly just a friendly conversation, which is fun.

Dana Parish: So, congratulations on your grant. I found out about it all coming together because I saw it in Forbes and then in the LA Times, and then I saw it in the Financial Times and I was like, “Oh my God. This is front page news!” Can you talk a little bit about the work you’re doing in Long Covid?

Amy Proal, PhD: Covid? Yes! What happened is, for the past two and a half years or so—along with my close colleague Mike VanElzakker and a couple other scientists—we started a nonprofit research organization called PolyBio Research Foundation. We jumped into what we call the ‘infection associated chronic disease’ space. So those are chronic conditions initiated or exacerbated by infection, and those include ME/CFS which is a diagnosis in which patients get very debilitatingly ill after other viral infections beyond SARS-CoV-2, and—of course—chronic Lyme disease where we know that patients get bitten been by a tick, or who are sick with tick-borne pathogens, can become extremely debilitatingly ill. So, we were working in conceptualizing collaborative research programs and studies on those conditions, and then the pandemic began, and unfortunately, we knew that a subset of people was going to develop symptoms after Covid because every major pathogen, every major viral or bacterial pathogen, if you read the literature, has been connected to a development of chronic symptoms in a subset of patients.

So, it was very unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 was going to be different. We are taking a stand on the direction that our research is going to go in because as a group of scientists and some of the patients involved in our research team, we think that the most evidence that there is right now for the primary driver of Long Covid is the simple fact that it seems like patients may not be fully clearing the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In other words, the virus may no longer be easily identifiable in their blood, but it may hide in their tissue.

Dana Parish: Or the nasal swab or the throat swab or their saliva.

Amy Proal, PhD: Oh, yes, definitely.

Dana Parish: I think what you just said is the most important thing that people need to understand. That is not being heard and that is not being understood by the greater scientific community and by the public at large. It is unbelievable to me that that is the case because I think knowing that Covid persists in every single organ of the body, it can persist, it’s in the gut, it’s been found in cases where people had almost no symptoms and (in) autopsies. I mean, I think this needs to be talked about because why are we avoiding this virus or why do we care about this virus, if not for its long tail? Do you agree? Is this sort of in a realm of how you’re feeling about it as well?

Amy Proal, PhD: Definitely. So, you have this issue, and that is probably the single most important thing that you need to know if you study pathogen persistence in a chronic disease. Which is that fluids in the body, like blood, or like you said, the nasal fluid that you just swab when you’re trying to do a regular Covid rapid test, or often just regular saliva, urine, etc., those are the places that it is least likely for most persistent pathogens to be found over time. It’s just not a smart place to be in the fluids, especially in blood. The immune system is the most robust. There’s a lot of immune cells around, so it’s where you’re going to get targeted. So the pathogens, in simple terms, they hide and they burrow into nearby tissue, and then they persist there in what we call a ‘viral reservoir,’ like a little reservoir where they’re more shielded from the immune response, but they’re still able to produce protein and still continue to perpetually activate the immune system and also basically throw off even the way that human genes and cells are working in that area of the body that can have large flow on effects to the whole system.

Amy Proal, PhD: Definitely. So, you have this issue, and that is probably the single most important thing that you need to know if you study pathogen persistence in a chronic disease. Which is that fluids in the body, like blood, or like you said, the nasal fluid that you just swab when you’re trying to do a regular Covid rapid test, or often just regular saliva, urine, etc., those are the places that it is least likely for most persistent pathogens to be found over time. It’s just not a smart place to be in the fluids, especially in blood. The immune system is the most robust. There’s a lot of immune cells around, so it’s where you’re going to get targeted. So the pathogens, in simple terms, they hide and they burrow into nearby tissue, and then they persist there in what we call a ‘viral reservoir,’ like a little reservoir where they’re more shielded from the immune response, but they’re still able to produce protein and still continue to perpetually activate the immune system and also basically throw off even the way that human genes and cells are working in that area of the body that can have large flow on effects to the whole system.

So, that is the key—you can test someone with just regular blood tests and nasal swab tests, and they can seem like they do not have SARS-CoV-2 to you, and yet it could be in their entire tissues and brain. And that’s why our initiative is largely focused on the study of tissue. In our earliest projects we have an intestinal tissue study, a lung tissue study from patients with Long Covid, skeletal muscle, lymph node tissue. A bunch of tissue types in areas where you’d expect to find the virus. So that’s where we’re going to look for it: looking for the virus in what I would call the right place.

And the second thing of what you said (that I am responding to) is, yes, right now our government has basically placed the risk of how you think about getting Covid on the individual. Like, ‘Hey, do your thing.’ You know? Well, they (the government) make it seem… It’s crazy that most of my family members and friends think this. So, it is clear to me that this is public messaging, that the two things that basically you have to worry about (are) 1. dying and that’s obviously a big deal, or 2. you’re okay. And that utterly ignores what I consider (to be the most) concerning middle ground, which is a lifetime of debilitating chronic illness that is extremely hard to manage. And that’s what we’re studying, that’s the main consideration. And some of the unfortunate trends there we actually see, and that’s what we’re calling Long Covid, is the chronic illness that can result when you don’t fully get over Covid, that we’re actually just basically at this point, doing a lot of work on. It may simply be that people don’t fully clear the virus, which also is in a sense, a growing concern because SARS-CoV-2 is evolving around the immune response. So, it honestly seems from some of the early studies that it’s been capable of persistence in tissue from the beginning, from the earliest strains, but now you’ll repeatedly even see in the news ‘New immune-evading variant’ or ‘Omicron, or this Omicron variant is more immune-evading…’

Dana Parish: Can you talk about what that means? So just for the layperson, you know, (like) my mom who might be tuning into this now?

Amy Proal, PhD: When I say ‘immune-evading,’ what I mostly mean is that the virus continues to evolve the way that it is acting, so that it has mechanisms by which the immune system does not recognize it very much. So, when you are infected with a pathogen, there’s a whole series of events that should happen where you first have your earlier what are called the innate immune (response), they’re kind of like the foot soldiers of your immune system, like mast cells and neutrophils. They’re supposed to come in and be like, ‘Ah, like an infection,’ you know? And then they signal to what’s called adaptive response. It’s like your B-cells and your T-cells, and they bring them in, and all of this is supposed to happen when you’re infected, and that’s how you get rid of the virus. The immune system fights it off, but the virus—and it depends on the variant end of SARS-CoV-2 and depends on the research—is evading (it) so that it’s not recognized by various parts of the immune response there.

Dana Parish: So, what happens? What happens to you physically, you wake up and feel what? What happens in the long term?

Amy Proal, PhD: I mean, so that’s the issue and again, this needs more research, but just conceptually, a lot of times symptoms are the results of the immune system noticing a pathogen and fighting it. So, when you get a cold and you feel the symptoms and the fever often, or sometimes that you get with an infection, it’s because that’s the battle, the results of the battle between your immune system and the pathogen. If you don’t get many symptoms, it could be that you’re beating the pathogen, or it could be that your immune system isn’t recognizing it that much and isn’t able to fight it that much. And I think that needs more study. But we do know as a trend that a lot of patients who are developing Long Covid had mild or asymptomatic cases when they first got sick.

Dana Parish: Then there’s a period we need to talk about latency because this is another huge topic that is being ignored. I always call latency the elephant in the room. Can we talk a little bit about that? And if this was the same within chronic Lyme? This was my specific case: I got the (tick) bite, I recovered after three weeks of doxy (doxycycline). I caught it really early. Within five days I saw a rash. I was so lucky, treated with three weeks of doxycycline, and I felt okay. Two months later, all hell broke loose. Within five months I was in heart failure. So, I’m seeing very similar trends with Long Covid where people recover from a mild case: for a couple weeks, they feel a little, you know, cold, flu-like sniffly. And they tell me they recovered. Well, two months later, three months later, couple weeks later, whatever it is, I hear, ‘Oh my God, I’m so fatigued, I’m so winded. I’m having chest pain, I’m having trouble breathing, I’m having pain in my bladder.’ I mean, I have heard all kinds of body pain, new arthritis, tons of tinnitus, tons of hair falling out, all kinds of stuff that was not part of the initial flu-like illness. And I think that’s the thing that bothers me most is that nobody understands that there’s this latency period. What do you think about that?

Amy Proal, PhD: Yes. And again, we need to capture that more formally in studies, which is what some of our initiative studies are aiming to do, but just exactly anecdotally, if you talk to enough people, and especially people that start getting a Long Covid diagnosis or ending up at the doctor. You might get SARS-CoV-2, and it’s kind of mild and not a big deal at first. But again, if you didn’t fully clear the virus and a little bit of virus is still in your system, then that virus over time can likely spread to other body sites or potentially infect a different nerve or get into other tissue. And there are patients who actually say exactly what you said. I wasn’t that sick at first, but a month later I started to experience other symptoms. And then often those patients and other patients will even report that they have relapse and remitting type symptoms as well, which is common in chronic illness, where periods of symptoms feel a little bit better, but then they push themselves harder, they all break out again, they crash, they relapse when they crash, they get more flu-like symptoms.

And those are pretty good, you know, I’m going to call them anecdotal signs, but like when you’re thinking of symptoms that would occur when you’re just having fully cleared the pathogen that you got, those are some of the prime symptoms. So that’s the problem. I think there’s still what I guess is a misconception out there that you are more likely to get Long Covid if you were hospitalized, and you had a severe case. And those people also do, unfortunately, often become very chronically ill, I’m not saying that that’s not a big deal, but there is this lack of understanding that you can just get the mild case of Covid that doesn’t seem like a big deal, and then definitely continue to be sick down the line and possibly not clear the virus. And I agree with you that I hear this even from friends of mine who may not be making that connection where they’ll say, ‘God, I started get these new headaches,’ or ‘I can’t think straight,’ or, you know, ‘I’m getting diagnosed like you said, with pelvic pain or endometriosis’ or something like that. And, and they don’t connect it to the fact that they got Covid a month before and that might have been part of the problem.

Dana Parish: I’m also worried about the sudden deaths. I mean, it is not possible to ignore how many young, healthy people are literally dropping dead, walking down the street, on the playground, on the field, playing softball, playing football. It’s not normal. And marathon runners are like in the most incredible shape, you know, (experiencing) the blood clotting stuff. And I don’t think people are aware of that either. I think that (when) people recover from a mild case they’re not really being followed. They’re not concerned about strokes or aneurysms or heart attacks, and they’re getting them. I mean, and I’m not even sure what the right intervention is. My dad just had Covid and we’re talking, and one of his markers for blood clotting went way up. He feels okay, but nobody’s even sure what to do with it. You know, nobody’s sure how to treat these things. You can’t overly thin somebody’s blood. You know, there’s questions: Should everybody be on aspirin after they get Covid? I know doctors who absolutely think that, yes, they should. But you know, this is just such a diabolical virus that I’ve never seen anything like it.

Amy Proal, PhD: First, I’m sorry about your dad, that’s really difficult. And, you know, second, we do have a study that I’m excited about. It is one of our early Long Covid research initiative projects that UCSF is doing, looking for SARS-CoV-2 and proteins and belated immune and gene expression changes in what is called a sudden death cohort. They have access and they’ve built this program over time to be able to collect tissue from people in San Francisco who die sudden deaths, so sudden cardiac deaths, other deaths like that— sometimes also car accident deaths or drug overdose deaths. But that study then exactly allows us to begin to research what you’re saying and for example, when someone dies of a sudden cardiac event, can we find SARS-CoV-2 in their cardiac tissue?

Amy Proal, PhD: First, I’m sorry about your dad, that’s really difficult. And, you know, second, we do have a study that I’m excited about. It is one of our early Long Covid research initiative projects that UCSF is doing, looking for SARS-CoV-2 and proteins and belated immune and gene expression changes in what is called a sudden death cohort. They have access and they’ve built this program over time to be able to collect tissue from people in San Francisco who die sudden deaths, so sudden cardiac deaths, other deaths like that— sometimes also car accident deaths or drug overdose deaths. But that study then exactly allows us to begin to research what you’re saying and for example, when someone dies of a sudden cardiac event, can we find SARS-CoV-2 in their cardiac tissue?

That’s exactly why we’re doing that study. And I think as a second that it’s always hard to talk about autopsy work. We’re not at all glad that people are dying sudden deaths, but we at least can take advantage of that tissue and study it and try to understand what’s happening. And that makes it one of the most important studies I think that we’re doing. But I do think it’s also an important trend to understand that in addition to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which may likely not clear in someone who has chronic symptoms or who gets symptoms after Covid, the virus, SARS-CoV-2 holds down the immune response as part of its survival.

Dana Parish: So, it’s immunosuppressive, is that what you’re saying?

Amy Proal, PhD: Overall, most viruses and even bacterial pathogens are immunosuppressive to some degree. That’s part of how they persist. So, the immune system is always recognizing them and that makes it harder to stick around. They have mechanisms by which they make proteins and products that hold down the immune system, which allows them to hang out. SARS-CoV-2 does that via several mechanisms including knocking down in several ways, interferon, which are important proteins that are needed to control other viruses and even bacterial pathogens. So, what we’re seeing in research data is that other viruses and potentially bacterial pathogens are reactivating as well in many of these patients who get sick with ongoing Long Covid or potentially SARS-CoV-2 including the herpes viruses.

The herpes virus is being studied the most. We tend to study the herpes viruses the most, for example Epstein Barr virus (EBV) is a herpes virus. So, then it’s sort of self-fulfilling that we notice those that activate the most, but it is still a serious virus. And something that we know about those viruses too is that myocarditis or a lot of cardiac events are also known to be driven in many cases by other viruses. So, for example, several of the herpes viruses, Parvovirus 19, which is a virus that a lot of the population harbors that again is not discussed a lot but is a fairly common persistent pathogen that people harbor, like the herpes viruses, they’re all known to be able—if they get into the heart tissue—to also drive symptoms in and of themselves. So, you could also have a situation with cardiac issues where SARS-CoV-2 is holding down the immune response and even other viruses are taking advantage of that. And that’s also contributing to cardiac events. So, you know, there’s a whole slew of issues there with what can happen.

Dana Parish: I’m kind of worried that there’s so much emphasis on viruses that bacterial infections like Lyme, which is also chronic, and Bartonella, are being swept under the rug. I personally get so much contact from the Lyme community patients who recovered from say Lyme four or five years ago, like me, then when they get a Covid infection, all their Lyme symptoms come back. They re-treat the Lyme and they get better. Now, not all of them, but I’ve heard this so many times at this point that I have to take it really seriously. You know? Do you think that Lyme and Bartonella and other pathogens that are bacterial are also reactivating in the face of Covid?

Amy Proal, PhD: Yes. I don’t see why that wouldn’t happen. We are trying to understand if patients with Long Covid harbor tick-borne pathogens, and by that, I mean the parts of the immune system that SARS-CoV-2 suppresses but that will allow other viruses to reactivate. But there’s similar components that also allow bacteria to reactivate. So, if you already had Borrelia or Bartonella your immune system may have kind of reached a point where it was contained, and you treated it somewhat and then you knocked down your immune system again with this new infection. I mean, of course the Borrelia or Bartonella or other bacterial pathogens or fungal pathogens or parasitic pathogens. One interesting fact that blows my mind is that 11% of the United States population is latently infected with toxoplasma, which is a parasite often acquired via cats. That latently infects the central nervous system. And so yes, 11% of us at least have this latent parasite that is connected to a major driver of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Dana Parish: I want to talk to you about that. It literally can change the way you think. It literally takes over your brain. A lot of that’s something we should talk about. People don’t appreciate how often infections can change your personality. They give you new onset anxiety, depression, psychosis, bipolar disorder. Terrible insomnia. You know, it’s so common. And yet doctors are trained to say, ‘Okay, so let’s try some antidepressants. Let’s try some Ativan or Xanax or whatever. And I have no issues with people taking any of these drugs, but I do think a deeper exploration of cause would help. For example, I got a severe case of Lyme and Bartonella and I had people probably not even believe me because they think I’m such a zealot on Twitter, always preaching about avoiding Covid.

But it’s because of what happened to me that I have this really strong need to protect patients from these kinds of things. So, for me it was incredible, intense, sudden, and neuropsychiatric problems in addition to physical problems. I had anxiety, depression, insomnia, OCD, I was literally hallucinating—picturing melting monstrous faces every time I closed my eyes. And I could have very easily been one of the cases that was written off as a psych case given a million medications. But instead, I was the lucky one who saw a tick bite, knew it was related, kept pressing for answers, and treated my Lyme thoroughly. After the three weeks of doxy failed, I went on to find Dr. Steven Phillips. He treated me for several months. And all my neuropsychiatric stuff went away. And (with the original infection) my personality changed. I was flat. You couldn’t make me laugh; you couldn’t engage me in anything. I was a shell of my former self. I’m seeing this again with Long Covid and I’m thinking there must be answers to clear these infections to get people better. I mean, are they coming? Do you think that there are cures and therapies that are going to work to clear these viruses and viral reservoirs out of people’s organs, like their brains?

Amy Proal, PhD: Yes, I do think we’ll get there. By the way, I would say that it makes sense if you’re a Long Covid patient and you get a Long Covid diagnosis, that you get tested for Lyme and Bartonella. Especially if you have neuropsychiatric symptoms. However, you must work with a doctor who knows how to order the right testing. It’s not going to really hurt you to do the testing and you might as well try to eliminate that from your case if possible. The testing’s not perfect, but I wouldn’t see the harm in doing that testing in case something turns up. I think one of the mistakes people make is they think, ‘Oh, my case is either. It’s SARS-CoV-2, or it’s Lyme, or it’s Epstein Barr virus.’ People split into communities, and they split into these different diagnostic labels. They’ll say, ‘I have ME/CFS.’ If there’s more – if they recognize the virus more in their case, or if their case started with SARS-CoV-2, then they’re a Long Covid case.

I mean, we get that, but overall, what happens is different pathogens mix and match into different cases. So, you could have had Bartonella that you didn’t realize that you got from a pet. Pets can transmit Bartonella, and you don’t even have to get a tick bite. You just can get infected from your pet and it maybe you were managing that, and your immune system was keeping it in check. Then maybe you also got an Epstein Barr infection and that is part of your case. And then you got infected with SARS-CoV-2. And when you got SARS-CoV-2, now it’s holding down the immune system and now the Bartonella and Epstein Barr virus are finally actually manifesting and driving more. You don’t have to be a SARS-CoV-2 case OR a Lyme case. There’s a lot of division there. What you want to do is investigate and test as much as you can for all the possible factors that might be contributing to your symptoms. And the more you do that, the more likely you’ll be able to find parts of your case that maybe you can work on clinically.

Dana Parish: Totally agree. And thank you for saying that. I think that is such an important message. And again, I do think it’s important to look at the viruses too. I also know from my experience in Lyme from writing the book and interviewing many doctors and scientists like you, that in the face of some of these reactivated viruses, there was a bacterial infection like Lyme that suppressed the immune system. It’s so common with Lyme patients to also have activated Epstein Barr virus and it’s also common that once they treat their Lyme, their immune system calms down and goes back to normal. Their Epstein Barr virus levels go down. So, I think again, we must keep looking into these things and keep going further and further towards the root causes and there may be multiple hits, multiple roots, and I appreciate all of those things. I just want doctors to figure them out. Can you set the record straight? I kind of shudder when I hear the term ‘viral debris.’ I mean, what is the deal with viral debris? Is it even like a thing or are people just missing the actual virus that’s still replicating and they’re just ignoring it, or they don’t understand that that’s happening?

Amy Proal, PhD: Yeah, but I think it’s gotten better. When Covid started, we started to delve into the topic of people still potentially harboring SARS-CoV-2 in viral reservoir sites. You would get people who sometimes say, ‘Ah, it’s a viral fragment,’ or ‘There’s debris from the virus.’ And the truth is that those terms are not really accurate. I think that it comes from a place of people not understanding RNA virus persistence and behavior. It is an understudied topic and it’s not a topic that’s taught very often in medical school and other places. So, you have read the literature on RNA. For example, herpes viruses are DNA viruses. People know about those more and they understand the concept of latency with those. But RNA viruses are not discussed in that context very much.

Amy Proal, PhD: Yeah, but I think it’s gotten better. When Covid started, we started to delve into the topic of people still potentially harboring SARS-CoV-2 in viral reservoir sites. You would get people who sometimes say, ‘Ah, it’s a viral fragment,’ or ‘There’s debris from the virus.’ And the truth is that those terms are not really accurate. I think that it comes from a place of people not understanding RNA virus persistence and behavior. It is an understudied topic and it’s not a topic that’s taught very often in medical school and other places. So, you have read the literature on RNA. For example, herpes viruses are DNA viruses. People know about those more and they understand the concept of latency with those. But RNA viruses are not discussed in that context very much.

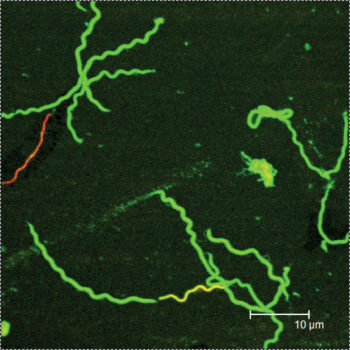

For example, Diane Griffin is a researcher on our Long Covid research initiative team, and she’s been studying for decades how measles virus in alpha viruses, which are other RNA viruses, can persist for long periods of time in animal models that she works on in the lymph nodes. And this is a very common thing that measles virus can do, but if you haven’t read her papers, it’s such a narrow topic, you don’t really know that. People are not familiar enough with the way RNA viruses can also stick around and when they’re not (familiar), they come up with those terms. That’s the best thing I can say about debris or particles or something. I think what they’re struggling to come up with (is) a way to explain the persistence, but it’s not accurate.

What you want to say is that the genetic material of the virus is still there. A virus is made of a genetic backbone and when we find it in samples later, that’s what we find. We don’t find a piece of it, or it’s not all mushed, it’s just still there. So, we can eliminate those terms, debris, and fragments from the discussion. We don’t need them. They’re not accurate and it’s a lot easier to talk about this with the right terms.

Dana Parish: It’s a lot easier for patients and clinicians. And for scientists that are entering the field and want to learn and treat Long Covid or study Long Covid to understand how common pathogen persistence is. It’s a topic that is not taught very well or very often in medical schools. I’ve talked to infectious disease doctors who have learned through seeing patients and through people like you and through reading all these papers that, ‘Oh my god, so much of what I learned in medical school wasn’t even correct.’ The whole concept of autoimmunity. How infections and other environmental hits are huge drivers of autoimmune disease, including MS. Fibromyalgia is not technically autoimmune, but we talk about it under that umbrella. And all the psychiatric stuff that we talked about, like interstitial cystitis, you know, these things that people think have no cause and their doctors often think have no cause often do have a cause that’s treatable like an infection. Again, for me, it was Lyme and Bartonella. For other people it’s different things. What is your position on the underlying causes of autoimmunity, and do you agree that they have underlying causes or is the body attacking itself in the absence of an invader?

Amy Proal, PhD: They have underlying causes. I do think that the theory of autoimmunity, and I’ve written about this a lot, was developed, or created at a time when the human body was considered to be largely sterile. In the sixties and seventies (the thinking was) that the immune system was activated in a person with MS or arthritis or an auto autoimmune condition. You just captured that something was happening in the immune system and then it was easy to blame the immune system. It was a straightforward thing to do. And that concept of autoimmunity, of like your immune system just failed on you and is attacking you, really does have more of a basis in legend than in reality.

In other words, this whole idea that your immune system would turn against you is a theory of autoimmunity and I think people should consider that in the name. It was what was speculated to be happening then when we didn’t have more information. And in recent years, especially in the last 10 years, the technology that we can use to identify pathogens in the human body, in human tissue and in body sites has just improved by orders of magnitude. We can now use computers to identify organisms. What that means is we take a sample, and we just extract all the genetic material there and we use computers to map that too. We can see all the sequences that can pertain to organisms or pathogens in that sample. And that has revolutionized our ability to find pathogens in the human body because before you had to try to culture them in a dish or just do things that they don’t grow that way.

So, we can now find pathogens in ways we couldn’t before. So, what needs to happen and is happening is that now we’re beginning to connect these immune responses in patients with so-called autoimmune disease to the presence of pathogens that we’re increasingly just better at identifying in those patients. With MS being a good recent example where two studies, one from Harvard and one from Stanford, tied MS now conclusively to Epstein Barr viruses, at least one of the viruses or one of the pathogens that’s really connected to the disease. And importantly in the Stanford study, they showed a mechanism that’s important to try to understand when it comes to connecting autoimmunity to infection, which is that often pathogens make a protein, and that protein can be similar in size or shape to a human protein or a human structure.

And so, what can happen is the immune system targets the pathogen protein like Epstein Barr virus protein, and then it cross reacts with a human protein as well. And, and then that is in a sense leading to targeting of human tissue. But the reason the human protein or tissue got targeted was because the immune system was firing on the pathogen first. So, it’s kind of like if you were in an army and the enemy was dressed in red and you were supposed to be firing on the enemy in red uniforms, but there are also civilians wearing red too, and you hit them too. That’s a little of what happens is the immune system is trying to target the pathogen, but the human tissue is somewhat similar, so it hits it as well. So, there is that targeting of self, if you will. That happens, but the reason is the infection. So, if you get rid of the infection, you won’t target the human tissue anymore. The key step there is understanding that the immune system is likely targeting a pathogen first.

Dana Parish: (This is why) we are so vehemently opposed to calling chronic Lyme post-treatment, Lyme disease syndrome because it implies that the infection is gone when it’s not. In some cases, it might be, I don’t want to make a blanket statement that everybody with ongoing symptoms has Lyme still that had Lyme infection. But there is a good amount of people that do. And I think that this whole notion of post viral syndrome (needs to be abolished), I think the semantics really inform treatment. They also inform how patients are looked upon by physicians because there’s a lot of like, “oh, it’s just in their head, the virus is gone, we can’t find it.” We talked earlier about how difficult it is to find because it’s being harbored and causing symptoms by being harbored in organs and you can’t really find those too easily. It’s not going to be found in the blood and it’s not going to be found in your nose or in your saliva. So, I think that we have to really talk about ending these damaging and harmful ways of describing disease processes, ongoing disease processes and stop assuming that they’re post. Do you also, do you agree? Is that fair that we should be calling it something else?

Dana Parish: (This is why) we are so vehemently opposed to calling chronic Lyme post-treatment, Lyme disease syndrome because it implies that the infection is gone when it’s not. In some cases, it might be, I don’t want to make a blanket statement that everybody with ongoing symptoms has Lyme still that had Lyme infection. But there is a good amount of people that do. And I think that this whole notion of post viral syndrome (needs to be abolished), I think the semantics really inform treatment. They also inform how patients are looked upon by physicians because there’s a lot of like, “oh, it’s just in their head, the virus is gone, we can’t find it.” We talked earlier about how difficult it is to find because it’s being harbored and causing symptoms by being harbored in organs and you can’t really find those too easily. It’s not going to be found in the blood and it’s not going to be found in your nose or in your saliva. So, I think that we have to really talk about ending these damaging and harmful ways of describing disease processes, ongoing disease processes and stop assuming that they’re post. Do you also, do you agree? Is that fair that we should be calling it something else?

Amy Proal, PhD: Yes, I don’t think post-viral or post-infectious or post-you-name-it-whatever syndrome is a good name because post means after—that’s largely what the word means in that context. And so, what you’re basically saying is: ‘after this infection,’ when what’s turning out to be the case is it seems like an ongoing case of that infection is the central theme we’re actually studying. So that’s why we use the term ‘infection associated chronic disease’ where we’re saying this condition is associated with infection and we go from there. That’s what we’ve been using instead.

Dana Parish: I love that term. It’s so much more accurate and it really makes people think differently about what might be going on. I don’t know why I must keep reading ‘post-viral’ and ‘post-infectious.’ We’re always screaming about it and like (it) just keeps happening. There are hundreds of studies now that document viral persistence with Covid and reactivation. Can we talk about whether anybody is predisposed to getting Long Covid? Are there certain markers or certain identifying features of people? Are you seeing trends?

Amy Proal, PhD: Yes, that’s a good question. Definitely I would pay attention to infectious history. Like we said, if you already have another latent infection and that pathogen’s probably already holding down your immune system a bit, you might be more susceptible to getting infected with SARS-CoV-2, in a way that it’s harder to clear that infection as well. I actually have written about that before and called that successive infection where really once you get one pathogen and it doesn’t fully clear, it’ll be somewhat immunosuppressive in order to facilitate its survival. And then that might make you a little less likely to clear the next infection that you get because the immune system isn’t as robust and then that pathogen will also hold on to the immune system and then it might make you more susceptible to the next pathogen. Right? So now you get a little bit of a ‘snowball rolling down a hill’-type phenomenon where each infection is facilitating the next to a point, which is something you’ll see in cases of Long Covid or ME/CFS.

In some of our studies we’re beginning to be able to document reactivation of other pathogens. And that theme already suggests that that’s happening, is that you would’ve harbored that pathogen already. The other thing to think about is the human microbiome itself. We’re all seeded with trillions of interacting ecosystems of organisms in most body sites. So, it used to be thought that we just had these microbiome ecosystems that are bacteria fungi viruses called bacteriophages in the gut, in the mouth. But now we understand that the lungs harbor microbiomes. Most of our tissues (harbor microbiomes) kidneys, you know, the bladder, there are existing organism ecosystems. And when you’re in a state of health and your immune system is functioning well, those ecosystems are usually kept in check. So, they’re kept in a state of balance like if there was a rain forest or something, a lot of the animals in that forest have the capacity to cause a lot of harm.

But since they’re all eating each other and they’re all in their healthy relationships, basically the forest is functional, right? But if you begin to deplete all the bears or something, there’ll be an overgrowth of (something)—that easily happens with human ecosystems as well. And so, one of the things that is a big predisposing factor to single pathogen infection, like SARS-CoV-2, is that if the microbiome in the lungs might already be in balance or not in good shape at the time you’re infected, that might make it easier for SARS-CoV-2 to take hold in your lungs more. Because more balanced communities tend to be more robust, often more diverse.

So, they’re actually in your tissue in these niches. And when SARS-CoV-2 comes in, they’re like, ‘Hey, no, no, no, we’re, we’re here!’ They’ve colonized more. Whereas when communities are unbalanced, they tend to be depleted. That in a simple term almost gives a little bit more area for SARS-CoV-2 or a pathogen to infect. But also, sometimes organisms in those communities produce compounds that target other organisms, just it’s part of their survival or their byproducts. They want to keep their niche again so they produce compounds that can sometimes be detrimental to other infectious agents and things like that. So certainly, that’s another trend we’re studying—for example, the gut as well. If your gut is already not in great shape and for example you even have fungal overgrowth or already have some overgrowth of other potential pathogens or imbalanced organisms in the gut, that might already create an atmosphere where it’s a little bit easier for SARS-CoV-2 to stick around in that environment as well and in the tissue and not clear. So certainly, microbiome health at the time of infection is probably a predisposing factor as well.

Dana Parish: Is there anything we can do to prevent Long Covid? I think most people don’t realize that they are harboring tons of asymptomatic infections. EBV is so ubiquitous in the population. Lyme is extremely common, and most patients are asymptomatic, or a good portion of people are asymptomatic. They may not have manifestations of it for their entire lives or it may happen 20, 30, 40 years later in the form of different dementias and stuff like that. So, given that so many of us are afflicted with these prior hits, is there a way to prevent you know, SARS-CoV-2 really taking hold and taking safe harbor in our bodies?

Amy Proal, PhD: That is a good question. The first thing I would say is try not to get Covid. I know that it’s really hard these days mentally to be spending all our waking hours studying Long Covid when everyone’s just getting infected again and again and not even understanding this is a thing. So, the first thing would be if less people can get Covid, we could start there. But then once you’re infected, that’s a good question. I do think that right now we’re in a place where we’re trying to understand how well certain antivirals work for SARS-CoV-2. So, it’s good because there hasn’t been a lot of antiviral development in the pharmaceutical space recently.

I had lunch with someone from one of the bigger pharmaceutical companies in Boston who was telling me that antivirals and antimicrobial in general have just been deprioritized over the past five to 10 years by pharmaceutical companies just generally, which is really mind blowing considering how much research is showing that that viral and bacterial pathogens are implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. And it should be the most robust area of pharmaceutical development that there is. Covid actually has started to change that a bit. We’re finally seeing pharmaceutical companies that make immunosuppressive drugs or therapeutics trying to develop an antiviral. So that’s encouraging. And I think we’re going to see (more), you know—Paxlovid is interesting. It seems that it can help some people, but I think we need a little bit more understanding of the rebound effects and how effectively it does fully clear the virus. And we don’t know necessarily how well it may help with clearance. It’s an open question.

Dana Parish: I don’t think five days is clearing it. I’ve talked to immunologists about this as well, it’s not just me saying it.

Amy Proal, PhD: No, I know that’s a concern because you asked about treatment before for Long Covid as well. And that’s one of the things we’re really going to have to think about and to the extent that’s possible have conversations with the pharmaceutical industry and the FDA about. That when you’re trying to target a pathogen—and especially a pathogen when it gets into a persistent state—short courses of antivirals or even antibiotics are unlikely to work. We know from related viruses and from research that longer courses of antivirals will likely be necessary and maybe even pulse doses of antivirals, where you take the antiviral (for a period of time, then), you give your immune system a break from it, (then) the immune system comes back up, you take the antiviral, and/or combining antivirals also with therapies that support the immune response. So, for example, if we know that the virus is knocking down T-cell responses, is knocking down those interferon signaling molecules that are important to the extent that we can create therapies that help support the immune system to bring those aspects of its function back as well, combining that with an antiviral makes a lot of sense.

In other words, (this means) targeting the virus itself while helping the immune system function as well. But to do that, we’re going to have to do clinical trials where we combine different therapeutics and that hasn’t been done that much. And, and I think we’re really going there with our initiative. We do have a clinical trials group that’s part of our team and part of what we’re working on is trying to make Long Covid the one of the first diagnoses where this actually happens, where we actually start to trial not only root cause treatments like antivirals for example, like trying to target the actual problem, but also trying to understand how to dose those drugs in a way that most makes sense, which almost everyone agrees at this point would have to be longer courses or pulse courses or combinations of antivirals. And even considering combining those with immunotherapies immune modulating drugs that might help support the immune system and to what extent can we use Long Covid to usher in an era of clinical trials and treatments in which this becomes the case for how we operate. And that is one of the things we’re really actually trying to work on right now.

Dana Parish: I’m thinking about this grant that you just got. I just so appreciate what you’re doing for the world and what this research is going to do for the greater chronic illness community. I mean, it’s ME/CFS, it’s chronic Lyme, it’s people with autoimmune diseases that are still suffering and not really getting much relief from palliative medicines. I’m just blown away that you’ve managed to put this whole thing together and just take it right to the top. So quickly before we wrap up, I just want to know what you still need. Like how can we help you get to where you need to go so that you can help us selfish people who want your help in finding answers to these horrible, debilitating maladies?

Amy Proal, PhD: Yes, I appreciate that, Dana. First, I do want to clarify that our long-term vision is to absolutely move our same teams and our same tissue-based studies into ME/CFS and chronic Lyme and related conditions. And the reason that we’re moving first and Long Covid is because when Covid started most labs were shut down. And so, the only reason you could go back into your lab and work was if you were studying Covid. So, many teams went back and started studying the SARS-CoV-2 and what early became correctly studied with SARS-CoV-2 is what I call tropism for tissue. Just tissue contains the ACE2 receptors that the virus primarily uses for entry. And people got that with SARS-CoV-2, that the study of tissue—autopsy studies, biopsy studies were important.

So, we were able to work with these Long Covid teams most rapidly to iterate the tissue and autopsy and even imaging-based studies beyond the studies, beyond just blood that are so needed in these conditions–there wasn’t as robust an ability to grow rapidly in ME/CFS or chronic Lyme. But the goal is to take the same infrastructure, the same similar tissue samples, similar teams, to move into the related viruses, for example, and take viruses, our RNA viruses strongly implicated in ME/CFS that are like SARS-CoV-2 into the tick-borne pathogens. And also, into Alzheimer’s, even longevity research, where aging is influenced by the pathogens and infections that you accumulate over a lifetime.

Dana Parish: Absolutely. We’ve heard a lot from Long Covid patients lately, about how much they feel they’ve aged. I felt that with Lyme, and I can see it in people a lot—and just the stress of all of this. And knowing what you know about Covid, is it a blessing or a curse? Does it make you more concerned about living in the world? Does it make you feel more worried about your family? How do you go through the world knowing all of this?

Amy Proal, PhD: I do think we have the research teams and paradigms and technologies to begin to study it robustly and comprehensively. As part of our initiative, some of the most cutting-edge technologies that can find pathogens in tissue via several mechanisms. So, a lot of what our projects are doing is not just looking for the virus, they’re actually pushing the boundaries of how we use the technologies themselves that we can then iterate into other pathogens more easily, more rapidly. So, that is constantly the entire vision of what we’re working on. And I guess just directly right now at this exact point in time, we did, as you said, get a $15 million donation to begin our research program from Vitalik Buterin and his Balvi fund who have been amazing. (It’s the) fund that Vitalik set up to fund high impact projects related to Covid.

And we’re honored that they chose our initiative and our projects as part of the largest donation that they made. And it’s been amazing. Our research program is broken into phase one, phase two, and then we have a little bit of extra money that we’re raising as well for research to just continue to help us iterate more. With every discussion that we have, we’ve grown new collaborations and projects out there just to keep moving. So that donation funded phase one, phase two is already delineated and contains some awesome projects that go beyond just the topic of persistence. We’re also studying (how) the virus does also seem capable of driving a lot of clotting processes—brain and deposition. So, a lot of the projects in phase two go into what we’re calling the downstream consequences of persistence or related to persistence. So, changes in VA nerve signaling, changes in cerebrospinal fluid flow, with cool studies to be able to tie those trends also into what we’re learning about the virus in patients.

Dana Parish: Any parting words? Anything I didn’t ask you that you wanted to talk about or that you wanted to say? Any hope for Long Covid patients that you want to impart? Any wisdom?

Amy Proal, PhD: No, I think you did a great job with your questions, and I feel that we got through our focus on tissue, our focus on studying the virus and root cause drivers themselves and the ability for us to iterate our program into the study of other persistent pathogens, which is just pretty much one of the most important topics in research right now. So, I think those are our main goals. And because you’ve written so well about those topics yourself, with your book Chronic and with a lot of the other work you do, you usually just ask me good questions. Thank you!

Dana Parish: Thank you for joining us for this episode of Ticktective, a program of the Bay Area Lyme Foundation. For more information and to get involved, visit bayarealyme.org.

This blog is part of our BAL Spotlights Series. It is based on a transcript from Ticktective, our podcast and video series. To listen or watch the original conversation, please click here. Bay Area Lyme Foundation provides reliable, fact-based information so that prevention and the importance of early treatment are common knowledge. For more information about Bay Area Lyme, including our research and prevention programs, go to www.bayarealyme.org.