The following is a post from a guest author, Dr. Michael J. Yabsley, MS, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Population Health at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia and Board of Directors, Companion Animal Parasite Council.

The following is a post from a guest author, Dr. Michael J. Yabsley, MS, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Population Health at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia and Board of Directors, Companion Animal Parasite Council.

He shares some important observations on the relationship between our pets and their people, especially in the context of vector-borne pathogens like Lyme disease.

Pets are our companions. They share our lives, our homes and our family time. We often share the mutual love of activities such as hiking or simply playing fetch in the backyard. While companionship is clearly why we have pets, our bond with them is often far greater than we appreciate — we share the same environment and more often than not, the same health concerns. At the top of this list are several vector-borne diseases.

Vector-borne diseases are those diseases transmitted by biting ticks, fleas, mosquitoes, and flies that feed on people and animals. These vectors transmit a plethora of pathogens during a blood meal, and some of these pathogens can cause diseases such as Lyme disease, Ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, and Heartworm disease. These particular diseases are zoonotic, meaning they can affect both humans and animals. Veterinarians have long recognized the close ties between our pets and their environment, and as a result we test annually for vector-borne disease infection and recommend use of Heartworm, flea, and tick preventives. Annual testing allows us to monitor an animal’s health, accepting they will, in all likelihood, be exposed to vector-borne disease agents on an ongoing basis.

Veterinary medicine has led the way in driving the fundamental principle that we are at one with our environment. The World Health Organization estimates that greater than 50% of the world’s population is at risk of vector-borne disease, and these diseases now constitute 20% of the burden of infectious disease worldwide. We must also recognize that there is no dividing line between human and animal health — we are one world. Our science is one science, our medicine is one medicine, and our health is one health.

Veterinary medicine has led the way in driving the fundamental principle that we are at one with our environment. The World Health Organization estimates that greater than 50% of the world’s population is at risk of vector-borne disease, and these diseases now constitute 20% of the burden of infectious disease worldwide. We must also recognize that there is no dividing line between human and animal health — we are one world. Our science is one science, our medicine is one medicine, and our health is one health.

All scientists, whether focused on human or veterinary health, understand that the ecology of vector-borne disease is incredibly complex because blood-sucking vectors, the pathogens they carry, and the various hosts that harbor these pathogens are dynamic and ever changing. Ticks, fleas, and flies can move considerable distances and be introduced to new geographic areas by human travel, international commerce, animal movement, migratory birds, and encroaching urbanization. Beyond human- and animal-related factors, we now know rainfall, heat, humidity, and wind patterns are also key determinants for the spread of vector-borne disease. The complex epidemiology of these agents makes surveillance, early detection, and prediction of emergence the most viable solutions to control vector-borne disease.

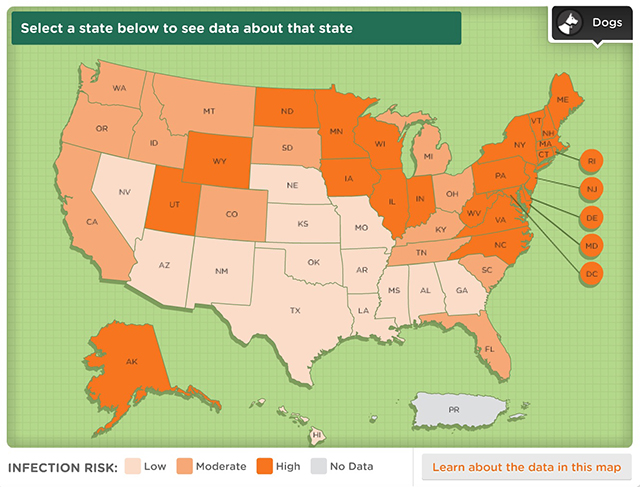

To address the growing need for surveillance and early detection, the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) has developed canine vector-borne disease prevalence maps in the United States (US). Importantly, the tick-borne diseases are diagnosed in both humans and dogs. Prevalence maps are developed by CAPC through compilation of millions of annual test results from veterinary practices across the US. The prevalence maps for Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and Ehrlichiosis report the percentage of dogs that have antibodies against these organisms (termed seroprevalence) and Heartworm disease reports the prevalence of detection of actual worm antigens.

Antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi (the causative agent of Lyme disease) are detected using the C6 antigen as the target and importantly, this assay does not detect Lyme disease vaccine-induced antibodies. Seroprevalence against B. burgdorferi is interpreted by veterinarians as exposure to the pathogen, and this knowledge is then used in combination with clinical signs of disease to guide treatment. Veterinarians use CAPC vector-borne disease prevalence maps across the US as evidence-based guides for risk in their local area.

While veterinarians clearly see the power of documenting infectious disease prevalence in protecting their patients, the outstanding question is whether we can apply canine data to human health, most notable of which is Lyme disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) researchers recently published data showing that the presence of ticks Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus, the two most common vectors of Borrelia burgdorferi, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum, have expanded their endemic range by nearly 45% in the last 18 years [1]. Additional studies evaluated the relationship between canine and human disease incidence, including in which canine data seroprevalence against Borrelia burgdorferi was >5% [2, 3] and another in which seroprevalence was <1% [4]. The CDC, in collaboration with CAPC parasitologists, determined that areas in which incidence of canine seroprevalence was 5% or greater was indicative of potential human exposure while 1% or less was not generally associated with human exposure.

As noted by CAPC Board of Directors President and Oklahoma State University parasitologist, Dr. Susan Little,

As noted by CAPC Board of Directors President and Oklahoma State University parasitologist, Dr. Susan Little,

“It is amazing when you realize that our pets are serving as sentinels, showing us where we are at risk for disease. It is a powerful demonstration of the strength and importance of the human-animal bond.”

While it is clear that companion animals may be sensitive indicators of vector-borne disease risk and provide an early warning system for public health intervention, more research is needed. When we consider the historical ebb and flow of canine seroprevalence against Borrelia burgdorferi across the US, we see dynamic annual shifts in incidence of canine seroprevalence between 2.5-5%. With more extensive research into the link between canine and human disease, especially in those regions where seroprevalence is between 1-5%, we expect the predictive power of canine data will help predict the emergence of human Lyme disease. This data, in turn, will give physicians an evidence-based tool to monitor the spread of infection and may prompt earlier testing for human Lyme disease. As we all know, early diagnosis and treatment is critical to prevent the long-term, debilitating effects of Lyme disease in humans.

Towards this end, CAPC has taken the next step to forecast the emergence of canine vector-borne disease, drawing on historical trends in disease prevalence and factors known to influence vector survival, such as climate conditions, socioeconomic characteristics, local topography, and vector distribution. We look forward to a greater convergence of veterinary and human medicine as our research progresses.

About CAPC

The Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) is a non-profit organization whose mission is to foster animal and human health, while preserving the human-animal bond, by generating and disseminating credible, accurate and timely information for the diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control of parasitic infections.

CAPC is an independent council established to create guidelines for the optimal control of internal and external parasites that threaten the health of pets and people, bringing together broad expertise in parasitology, internal medicine, public health, veterinary law, private practice and association leadership. Working closely with the animal health industry, CAPC’s overarching goal is to change the way veterinary professionals and pet owners approach parasite management via best practices, including annual testing and year-round protection, to better protect pets and their owners from parasitic infection. For more information visit http://www.petsandparasites.org/ and subscribe to our alerts.

- Eisen RJ, Eisen L, Beard CB: “County-Scale Distribution of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Continental United States,” Journal of Medical Entomology, 2016.

- Mead P, Goel R, Kugeler K: “Canine Serology as Adjunct to Human Lyme Disease Surveillance,” Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2011, 17(9):1710-1712.

- Little SE, Heise SR, Blagburn BL, Callister SM, Mead PS: “Lyme Borreliosis in Dogs and Humans in the USA,” Trends Parasitol 2010, 26(4):213-218.

- Millen K, Kugeler KJ, Hinckley AF, Lawaczeck EW, Mead PS: “Elevated Lyme Disease Seroprevalence Among Dogs in a Nonendemic County: Harbinger or Artifact?” Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2013, 13(5):340-341.

Thank you for a very interesting article!

If my dog came down with Lyme disease last summer, is he always going to have this in his system potentially flaring up again like chicken pox/shingles or did the antibiotic month long treatment “cure” him??

Bay Area Lyme is not a clinical organization and unfortunately can not advise on individual cases — pet or human — but, in general, early and thorough antibiotic treatment is highly effective at fighting Lyme. The key is getting an early and accurate diagnosis and treatment. We would advise you consult your veterinarian for more specific counsel. Best wishes.