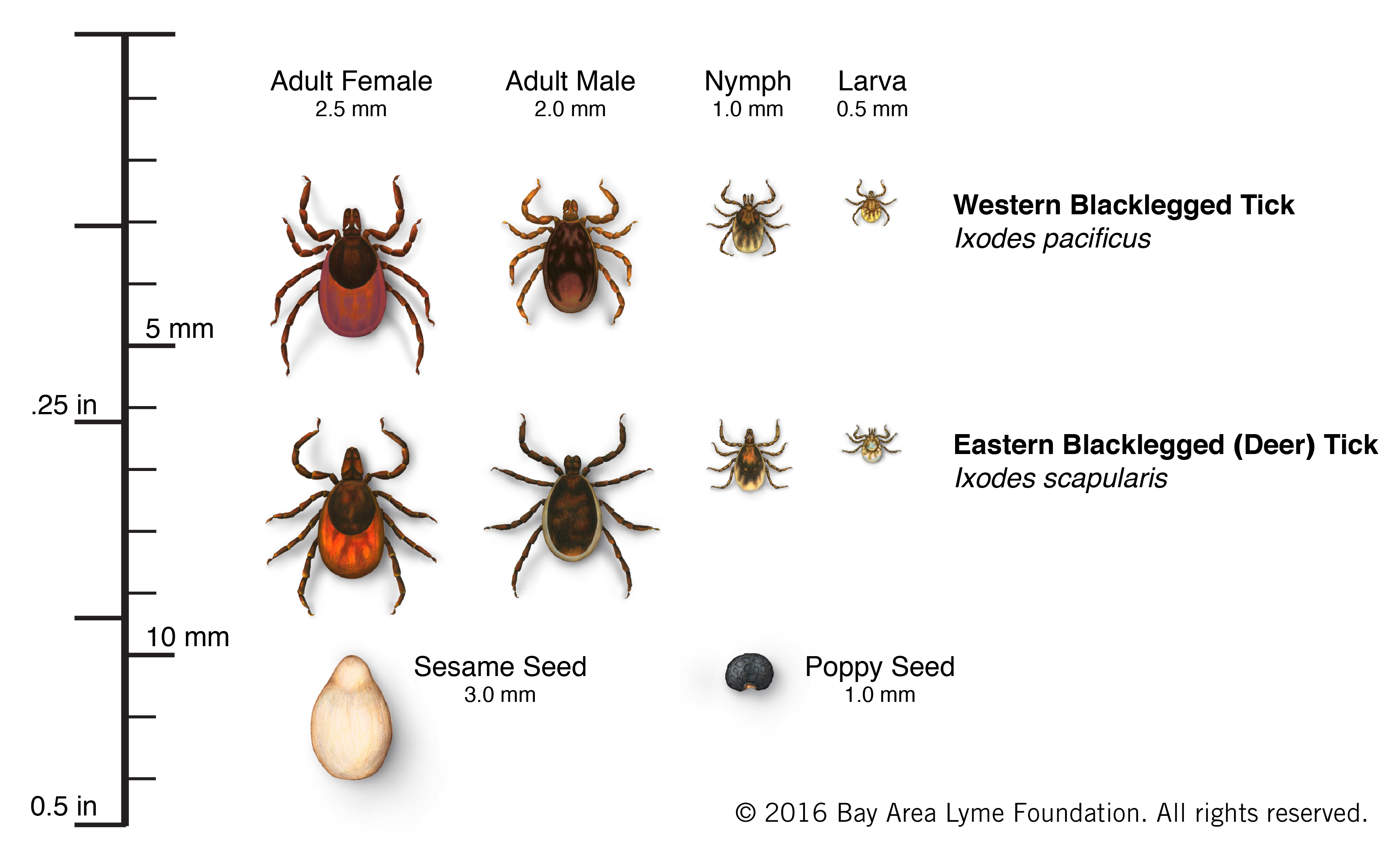

Blacklegged ticks (the eastern version, Ixodes scapularis also known as “deer ticks,” and the related western version Ixodes pacificus) are much smaller than dog ticks and are responsible for transmitting many bacterial diseases such as Lyme disease, Babesiosis, Ehrlichiosis, and Anaplasmosis (also see Other Tick-Borne Diseases for more information).

How Ticks Spread Disease

Ticks generally live two to three years and have four life stages. They must have a blood meal from a new host at every life stage in order to survive. The feeding process is lengthy and can last for several days. During this process, ticks can both ingest from and transfer bacteria into the host.

It does take time for the Lyme bacteria to travel from the tick to the host and it is generally believed that if the tick is removed within 24 hours, the likelihood of infection is minimal. Other pathogens (e.g., Powassan virus) can transmit in as quickly as 15 minutes.

How Ticks Attach

Blacklegged ticks cannot fly or jump but instead wait for their hosts by “questing” or positioning themselves on grasses or other greenery with their front legs outstretched, ready to grab a ride. As the potential host brushes by, the tick grabs on with the outstretched legs and then crawls to its destination.

Once the tick attaches, it pierces the skin and inserts a feeding tube. The tick also releases a cement-like substance helping it to stay attached during feeding and an anesthetic-like substance numbing the skin of the host and reducing likelihood of discovery.

Tick Life Stages

Ticks have four distinct life stages and must feed at each life stage in order to progress to the next.

Eggs

Female ticks lay a single egg mass with as many as 2,000 eggs in mid to late May, and then die.

Larvae

Larvae emerge in early summer and are active July-September. Barely the size of a printed period at the end of a sentence, the larvae generally remain in the leaf litter waiting to attach to nearly any accessible mammal or bird (preferred hosts are white-footed mice). The ticks will feed on their host, then drop off and molt, re-emerging the following spring as nymphs.

Larval ticks are generally believed not to be infected nor able to transmit disease to their hosts, and therefore not a threat to humans or pets, though they can ingest bacteria from their host. (Notably there is emerging evidence that Borrelia miyamotoi—unlike Borrelia burgdorferi—can be transmitted directly from the adult female to its offspring. See Cary Institute interview with Dr. Rick Ostfeld for more on this topic.

Nymphs

Nymphs are active May-August of the following year, and are also commonly found in moist leaf litter in or around wooded areas. These only slightly larger nymphs (about the size of a pin head) typically attach to smaller mammals such as mice, voles, squirrels, and chipmunks, but will readily attach and feed on humans, cats and dogs. Once fed, they also drop off and molt, emerging as adults in the fall. Most people are infected during the tick’s nymphal stage as likelihood of detection is much lower than in the adult phase.

Adults

Adults are generally active October-May if daytime temperatures are above freezing. Females feed then drop off into the leaf litter where they can over-winter, laying their eggs in late spring. Adult males do not feed at this stage.

Photo courtesy of Anand Varma

Image courtesy of Emily M. Eng